Making General Education Visible

How visible is general education? Assessment has shown us the importance in education of being more transparent, of articulating learning outcomes and providing evidence of learning. Russian Formalist Shklovsky (1965), when describing art, used a metaphor that translates into English as “make it stony.” To make something stony is to defamiliarize it, causing us to pay attention and perceive it anew. This project started with our interest in seeing just how “stony” general education is at American institutions of higher education.

Making education visible benefits everyone in the learning transaction—the student, the faculty, the public. Assessment has always had a double purpose, for both accountability and learning. From an accountability perspective, making learning visible holds institutions accountable and facilitates student and parent decision-making. Making learning visible for accountability has been the focus of the Transparency Framework at the National Institute of Learning Outcomes Assessment (or NILOA) (NILOA Transparency Framework). Here, transparency is not just a metaphor: their project focuses literally on what universities show in their websites about learning, about learning goals, and about learning results. This focus on transparency is seen in the NILOA work, Learning that Matters, which argued that communication is the final and crucial piece in the new learning paradigm (Jankowski & Marshall, 2017, p. 52).

From a learning perspective, making learning visible strengthens learning and facilitates transfer or generalization. When students know what they’re supposed to be learning, and when they can articulate those goals, they are more likely to achieve learning that sticks. (Brown, Roediger, & McDaniel, 2014). A large body of research on transfer supports these claims. The classic explanation of “high road transfer” (that is, the transfer of knowledge between greatly dissimilar contexts) has indicated that transfer is more likely when, among other things, the content being learned is articulated explicitly (Salomon & Perkins, 1989). High road transfer requires deliberate conscious abstraction of how to apply something learned in one context to another. A popular book on learning called this “thinking slow” (Kahneman, 2011). Likewise, Wiggins (1998) has explained that understanding – the ability to use knowledge in new situations – occurs when the teaching, the learning, and the assessment of material invite students to articulate connections and to explain “the big picture” (p. 94).

Along similar lines, a nationwide project, TILT, or Transparency in Higher Education (https://tilthighered.com), has demonstrated that courses that use transparent teaching strategies, such as teachers being explicit about their assignment objectives and debriefing assignments and tests in class, improved student learning (Winkelmes, 2013); and were associated with significant increases in three measures of academic success: academic confidence, sense of belonging, and awareness of improvement in employer-valued skills (Winkelmes et al., 2016). Perhaps the most frequent tool used to make learning goals explicit is the scoring rubric. Jonsson (2014) has shown that students find rubrics helpful, when those rubrics are effectively designed and deployed.

Making goals visible in general education may be especially important since learning, transfer, and generalization in general education pose a particular challenge. One purpose of general education courses is to introduce students to knowledge and skills they will be able to use later in advanced courses and their majors – i.e., learning they will generalize or transfer. (Beach, 1999). But as much as society, business, and faculty in almost every American college and university tout the benefit of general education courses, to students the general education curriculum often seems a hurdle of requirements that must be gotten through to get to their real interests in their majors (Hawthorne et al., 2010; Saadeddine, 2013). As Thompson et al. (2015) show, while students may mouth the principle that general education helps them become more rounded individuals when it comes to specifics, students do not see a link with either their current lives or futures.

Numerous studies (Adler-Kassner, 2014; Carter, 2007; Kirk-Kuwaye & Sano-Franchini, 2015; Russell & Yañez, 2003; Penrose & Geisler, 1994; Vander Schee, 2011) have proposed ways to help students in general education courses feel less like outsiders, more able to connect with these general courses, and more able to use them in later contexts. What these studies have in common is the recommendation to make more explicit disciplinary assumptions and the purpose of general education. This, in fact, has been the overarching theme and metaphor of the AAC&U “General Education Maps and Markers project” (GEMs), which proposes that general education will be more effective if general education goals are explicit and coherent, and if students understand and can articulate these goals (Gaston, 2015; General education 2015). But it’s important to recognize that AAC&U projects like GEM or NILOA projects like The Transparency Framework actually have faculty as their audience, not students. On the one hand this is because such organizations can only reach students through faculty. But on the other hand, and probably more importantly, while no general education program can exist without its faculty champions, faculty themselves are also often challenged by the purposes of general education. Even those teaching in general education may have limited knowledge of its structure, goals, or impact on student learning (Grob & Kueh, 1997; Cottrell et al., 2015). Their own ambivalence may then be passed on to their students (Thompson et al., 2015)

A review of the literature turned up little research on faculty perception of general education. The desire to increase student credit hours and recruit majors may often displace the ideals of general education. It is a reality that institutions offer general education courses to ensure stable enrollment and attract potential majors, not only to provide the skills and knowledge necessary for a well-rounded student and citizen. As a consequence, the goals of general education may not be very visible to either students or faculty at an institution. It is not an accident that the GEMs project is articulated as a metaphor – that is, that universities must create maps and encourage their students to create maps. A metaphor is one strategy for creating coherence. Metaphors connect the new to what is already known, and they entail other meanings that may help us see “the big picture.” Metaphors enable us to get a handle on something; they give coherence and meaning to our experiences (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980). The metaphors of a discipline or subject reflect its basic assumptions. (Postman 1995, pp. 173-174.)

This, then, is the background of our study: Research and theory suggest it is important for universities to make their goals explicit and visible. We want to know to what extent universities do that with general education.

Our research questions were:

1. How do institutions communicate their goals and values about general education to their students?

2. What types of representations do universities and colleges use to make the goals of general education visible?

3. What metaphors do institutions use to communicate about general education?

Method

Since the institutional website is often the first and only source of information about a university or college for those both within and outside the community (Civinini, 2019; Gardner, 2014; Tate, 2017), this inquiry focuses on evaluating university and college websites. We randomly selected 85 institutions of higher education and reviewed their websites for information about the institution’s general education curriculum.

Sample

Representative institutions were selected using the classifications on the Carnegie Classifications of Higher Education website, which listed the following institutional categories: R1 (N=115), R2 (N=107), R3 (N=112), Master’s: Small (N=146), Master’s: Medium (N=215), Master’s: Larger (N=415), Baccalaureate: Diverse Fields (N=326), and Baccalaureate: Arts and Sciences Focus (N=246). Five per cent (5%) of the institutions in each group were randomly selected, in a stratified random sampling framework. If a randomly selected institution that did not have English as the primary language, did not offer bachelor’s degrees, was no longer open for business, or was the authors’ home institution, another institution was selected to replace it. The final sample included 85 institutions.

Procedure

Two researchers visited each institution’s website. They searched for information on the general education requirements and goals. The researchers used three strategies: menus on the home page, institution website searches, and catalog searches. Using the menus, they drilled down no more than three levels until they located the general education content, starting with menus such as “academics” or “curriculum” or “requirements.” Using the institution website search bars, they used the term “general education” or, if that did not produce results, “core.” If neither of those strategies worked, they located the course catalog and either searched within it or used the table of contents or index (if they existed), looking for “general education,” “core,” or “degree requirements.” Five percent of the institutions were randomly selected for a reliability check. Inter-rater reliability was 80% for finding information on the general education program.

Information about general education was located on all but seven institutional websites. In the majority of cases (95% of the institutions), the way to find this information was by searching for the terms “core” or “general education” rather than by using menus. In 5% of the cases, searches revealed no information. The difficulty of finding information on the websites of institutions was classified into 3 levels. Easy meant that it was possible to find information about general education in one to two clicks when searching for the terms “core” or “general education.” A medium level of difficulty meant that the search for the two terms required probing beyond 2 clicks. Hard meant that the catalog had to be consulted to find information. In some cases, the catalog identified general education in the table of contents. In the most difficult cases, the only way to find information about general education in the catalog was through manual browsing.

Two coders identified visual and linguistic messages about general education on the websites. Only 6 out of the eighty-five schools used some kind of visual representation to describe or explain their general education requirements. Thus, there were too few visual representations to analyze visual messages further.

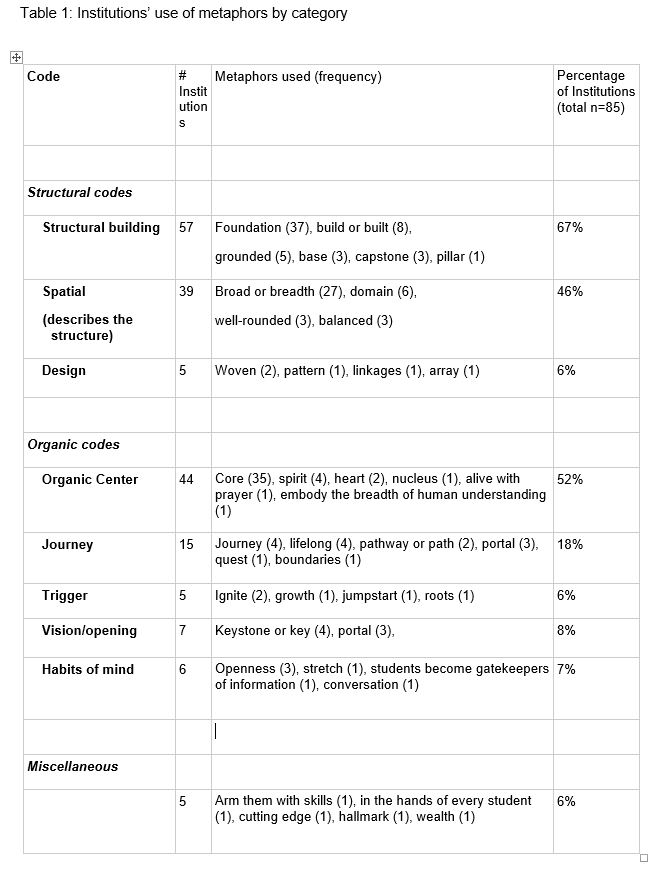

Passages up to 100 words were selected for review. The passages were the first 100 words in the description of general education at the institution. The two coders created a list of all the metaphors and grouped them based on conceptual similarity and function. Questions about what counted as a metaphor were resolved through discussion. Metaphors were grouped into two broad categories, structural and organic, and miscellaneous was used for the metaphors that did not fit the other categories. Subcategories were included within the broader categories. Some metaphors were categorized into two subcategories: portal, for example, was included in both the journey and the vision organic subcategories. The 100-word passages were compiled in a spreadsheet, and the search function in Excel was used to locate the terms. When a term occurred, it was counted once per passage.

Results

Our first research question was: How do institutions communicate their goals and values about general education to their students? Our data analysis focused only on the websites of universities and colleges. Information about the goals and values of general education was difficult to find. The highest percentage (44%) of searches was in the hard level, with 23% in the medium level and 32% in the easy level.

The second research question was: What types of representations do universities and colleges use to make the goals of general education visible? Primarily linguistic presentations were used.

The third research question was: What metaphors do institutions use to communicate about general education?

As seen in Table 1, two thirds of the metaphors in the language about general education on college and university websites were structural metaphors. From the perspective of faculty, the curriculum is an edifice, with general education on the bottom.

Dordt University, for example, states that the Core “gives students a stronger foundation …” [emphasis added].[1] And Stanford University says, “Students have flexibility to select topics that appeal to them while building critical skill sets” [emphasis added].[2]

A related and also numerous group of metaphors (46%) are what we called spatial metaphors (e.g., broad, balanced, well-rounded), and these are often used to describe the foundation or building. For example, the Core Curriculum at the University of Texas at San Antonio “helps develop broad skills that can be applied to any specific major or program [emphasis added].[3] The image one gets of the general education curriculum is of a pyramid – a wide base that supports a narrower top, presumably the major and upper-levels.

The other large group of metaphors, represented in 52% of schools’ websites, is the organic core metaphors, which focus on the core as the center of a student’s education. At Ursuline College, the core curriculum is “the heart of an undergraduate education” [emphasis added].[4]

Another group of organic metaphors, represented in 18% of schools’ websites, are those that focus on education as a journey. University of Missouri Kansas City promotes their new core by saying “you will connect with your university and Kansas City community, get the tools needed to learn here and throughout your life, and explore careers to find your rightful path” [emphasis added].[5] And at Grand Canyon University, “the knowledge and skills students acquire through these courses serve as a foundation for successful careers and lifelong journeys of growing understanding and wisdom” [emphasis added].[6]

Related to the metaphor of the journey, many of the less frequent metaphors focused on process. General education is described as an instigator or contributor to the development of the individual that occurs with education.

As in the language used at Grand Canyon University, where the foundation metaphor was combined with the journey metaphor, many schools used more than one category of metaphor. The Ursuline College Core Curriculum “is designed to provide the breadth of a liberal arts foundation” [emphasis added].[7] Likewise, Stanford says the general education (along with the major) requirements “serve as the nucleus around which students build their years at Stanford” [emphasis added]. [8]

What was common in the use of the metaphors was the message that general education provides a critical educational experience.

Discussion

This research addresses the overarching issue of the visibility and transparency of information about general education in institutions of higher education. Our first research question was how do universities and colleges communicate general education goals and values to their students? We approached this question by systematically measuring the ease of finding information about general education on each institution’s website. What we found was that it was not easy to find information about general education, even for two experienced faculty members. If institutions want to highlight their general education programs, making information easier to access is a place to start.

In order to answer the second research question, what types of representations do universities and colleges use to make the goals of general education visible, we examined the material published on the websites about general education. Most of the information about general education was linguistic. Very few sites used visual representations (pictures, schematics, etc.). This may be a missed opportunity, since visual representations provide another way to make meaning explicit and to promote learning (Chen, 2004, Raiyn, 2016). They have also been identified as a major method of communication both within the culture and academic disciplines (Williams, 2006).

Our third question was what metaphors institutions use to communicate about general education. We assumed that these metaphors were both indicators of institutional values and goals, with the potential to be teaching tools for students. When we analyzed these passages for the use of metaphors, we found that the most common metaphors were structural, referring to buildings and foundations; organic, referring to the embodiment of general education as a core, the center of learning; and spatial, referring to the breadth and depth of the structure general education provides. While these metaphors can communicate expectations about the goals and values of institutions regarding general education, we cannot be certain that the use is intentional. An intentional use of metaphors could be helpful in helping students make connections with general education, their majors, and their futures. The function of metaphor is to connect –something new to something old (Chen 2004) or one domain of experience to another (Lakoff, 1992).

If we use our metaphors intentionally in describing general education, perhaps we could then help our students understand these connections. First, faculty need to ask what decisions DO our general education metaphors reflect? What does it mean to say that general education is a foundation – usually broad and well-balanced – for something else to build on? How is that different from saying it is a heart or a trigger or a nucleus or a hallmark? The next step is to make the agreed upon metaphors visible. In many ways it is not surprising that for many students general education appears to be a random collection of requirements with nothing to do with each other or with what students really want to take in their majors (e.g., Thompson et al. 2015). Our difficulty in finding information about general education on institutional websites indicates that general education, while it may account for a number of credit hours students need to complete, is a “hidden figure.” If general education remains in the shadows, it is difficult to make its contributions clear.

Conclusion

General education remains an important component of the college curriculum, as evidenced by accreditation criteria and other regulations at both the state and national level. But in the current political environment where usefulness and efficiency are primary criteria for a good education, we should not take that for granted. We must continue to demonstrate the value of general education by

● Making general education requirements more accessible on university and college websites and catalogs;

● Interrogating the metaphors used to explain general education and use them intentionally in descriptions of requirements;

● Using these metaphors not just in websites and catalogs, but also in the courses themselves. For example, if a course is designed to be foundational, incorporate discussions of this foundation and what it is a foundation for. If a course is designed to trigger something, show how and what it triggers. At the same time, in the more advanced courses – link back to those foundations and triggers; and

● Considering multiple ways of representing our values and metaphors.

In short, we need to make general education “stony”.

Author(s)

Dr. Belinda Blevins-Knabe is a Professor of Psychology at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock. She is the former chair of the Core Council, which is charged with approving courses for the university core as well as developing and implementing assessment of the general education requirements. Other interests include faculty development for teaching and learning and assessment of the major. She served as co-director for the Academy of Teaching and Learning and has directed assessment of the psychology major for several years. Additional areas of research interest are student’s beliefs about general education, young children’s mathematical development, and the influence of the home numeracy environment on the development of early mathematics skills and concepts. She has a Ph.D. in Developmental Psychology from the University of Texas at Austin.

Dr. Belinda Blevins-Knabe is a Professor of Psychology at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock. She is the former chair of the Core Council, which is charged with approving courses for the university core as well as developing and implementing assessment of the general education requirements. Other interests include faculty development for teaching and learning and assessment of the major. She served as co-director for the Academy of Teaching and Learning and has directed assessment of the psychology major for several years. Additional areas of research interest are student’s beliefs about general education, young children’s mathematical development, and the influence of the home numeracy environment on the development of early mathematics skills and concepts. She has a Ph.D. in Developmental Psychology from the University of Texas at Austin.

Dr. Joanne Liebman Matson is a Professor of Rhetoric and Writing at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock. A former Director of First-Year Writing, she has been involved in general education and assessment for most of her professional career. Her other interests include rhetorical theory, writing across the curriculum, and legal writing. She is working on a large-scale study of how students learn to write in law school. She has a Ph.D. in English from the University of Minnesota and a J.D. from University of Arkansas at Little Rock.

Dr. Joanne Liebman Matson is a Professor of Rhetoric and Writing at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock. A former Director of First-Year Writing, she has been involved in general education and assessment for most of her professional career. Her other interests include rhetorical theory, writing across the curriculum, and legal writing. She is working on a large-scale study of how students learn to write in law school. She has a Ph.D. in English from the University of Minnesota and a J.D. from University of Arkansas at Little Rock.

Footnotes:

[1] All footnotes accessed in 2023 to assure viability of the link: Retrieved March 9, 2023, from https://www.dordt.edu/academics/core-program

[2] Retrieved March 9, 2023, from https://admission.stanford.edu/academics/undergrad/ger.html

[3] Retrieved March 9, 2023, from https://catalog.utsa.edu/undergraduate/bachelorsdegreeregulations/degreerequirements/corecurriculum/

[4] Retrieved March 9, 2030, from https://www.ursuline.edu/academics/undergraduate/core-curriculum

[5] Retrieved March 9, 2023, from https://www.umkc.edu/provost/umkc-essentials/prospective-students.html

[6] Retrieved March 9, 2023, from https://www.gcu.edu/sites/default/files/media/documents/academics/catalog/2022-23/academic-catalog-spring-2023-v4.pdf

[7] Retrieved March 9, 2023, from https://www.ursuline.edu/academics/undergraduate/core-curriculum

[8] Retrieved March 9, 2023, from https://admission.stanford.edu/academics/undergrad/ger.html

References

Adler-Kassner, L. (2014). Liberal learning, professional training, and disciplinarity in the age of educational “reform”: Remodeling general education. College English, 76 (5), 436-457.

Beach, K (1999). Consequential transitions: Sociocultural expedition beyond transfer in education. Review of Research in Education, 24, 101-139.

Brown, P. C., Roediger,H. L.. III, & McDaniel, M. A.(2014). Make it stick: The science of effective learning. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press.

Carter, M. (2007). Ways of knowing, doing, and writing in the disciplines. College Composition and Communication, 58 (3), 385-418.

Chen, E. H-L. (2005). A review of learning theories from visual literacy. Journal of Educational Computing, Design, and Online Learning 5 (Fall).

Civinini, C. (2019, March 7). Study profiles behavior of stealth applicants. The PIE News. https://thepienews.com/news/institutional-sites-crucial-to-recruitment-uniquest/

Cottrell, C., Cottrell, S., Wheatley, B.J., Dooley, E.A., & DiBartolomeo, L. (2015). Matching the purpose of the general education curriculum with the reality of its implementation. The Journal of General Education, 64, (1) 1-13. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/jge.2015.0002

Gardner, L. (2014, November 28). Your college’s new website Is student-focused, mobile-optimized, and probably long overdue. Chronicle of Higher Education, p. A8. http://0-search.ebscohost.com.library.ualr.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=99689265&site=ehost-live&scope=site

Gaston, P. (2015). General education transformed: How we can, why we must. AAC&U. Washington DC.

General education maps and markers: Designing meaningful pathways for student achievement (2015). AAC&U. Washington, DC.

Grob, L. M., & Kuehl, J. R. (1997). Coherence & assessment in a general education program. Liberal Education, 83, 34–39.

Hawthorne, J., Kelsch, A., & Steen, T. (2010). Making general education matter: Structures and strategies. New Directions for Teaching & Learning, 121. 23–33. https://0-doi-org.library.ualr.edu/10.1002/tl.385

Holba, A. M., Bahr, P. T., Birx, D. L., & Fischler, M. J. (2019). Integral learning and working: Becoming a learning organization. New Directions for Higher Education, 185, 85–99. https://doi.org/10.1002/he.20314

Jankowski, N. A., & Marshall, D. W. (2017). Degrees that matter: Moving higher education to a learning systems paradigm. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing. National Institute for Learning Outcomes Assessment (NILOA).

Jonsson, A. (2014). Rubrics as a way of providing transparency in assessment. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 39(7), 840-852.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking fast and slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Kirk-Kuwaye, M., & Sano-Franchini, D. (2015). Why do I have to take this course? How academic advisers can help students find personal meaning and purpose in general education. The Journal of General Education 64(2), 99-105.

Lakoff, G. (1993). The contemporary theory of metaphor. In Ortony, A. (Ed.) Metaphor and Thought, (2nd ed.) (pp. 202-251). Cambridge Univ. Press.

Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (2003). Metaphors we live by. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press.

McMurtrie, B. (2019, August 8). How students can promote the value of general education. The Chronicle of Higher Education Teaching Newsletter. https://www.chronicle.com/newsletter/teaching/2019-08-08

Musgrove, L. (2008, Winter) The metaphors we gen-ed by. Liberal Education. 94 (1).

National Institute for Learning Outcomes Assessment. (2011). Transparency Framework. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois and Indiana University, National Institute for Learning Outcomes Assessment (NILOA). https://www.learningoutcomesassessment.org/ourwork/transparency-framework/

Postman, N. (1995). The end of education: Redefining the value of school. New York: Vintage/Random House.

Raiyn, J. (2016). The role of visual learning in improving students’ high-order thinking skills. Journal of Education and Practice 7 (24).

Saadeddine, R. (2013). Undergraduate students’ perceptions of general education: A mixed methods approach (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Rowan University, Glassboro, NJ. https://rdw.rowan.edu/etd/390

Salomon, G., & Perkins, D. N. (1989). Rocky roads to transfer: Rethinking mechanism of a neglected phenomenon. Educational Psychologist, 24(2), 113.

Russell, D. R., & Yañez, A. (2003). ‘Big picture people rarely become historians’: Genre systems and the contradictions of general education. Writing selves/writing societies, edited by Bazerman & Russell. Fort Collins, CO.

WAC Clearinghouse. http://wac.colostate.edu/books/selves_societies/

Shklovsky, V. (1965). Art as technique. In L. T. Lemon & M. J. Reis (Eds.). Russian formalist criticism: Four essays. Lincoln: Univ. of Nebraska Press.

Tate, E. (2017, April 5). Colleges need to make websites easier to find info. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/digital-learning/article/2017/04/05/colleges-need-make-websites-easier-find-info

Thompson, C. A., Eodice, M., & Tran, P. (2015). Student perceptions of general education requirements at a large public university. JGE: The Journal of General Education, 64(4), 278–293. https://0-doi-org.library.ualr.edu/10.1353/jge.2015.0025

TILT Higher Ed (2014). Transparency in Learning and Teaching.

Vander Schee, B. A. (2011). Changing general education perceptions through Perspectives and the interdisciplinary first-year seminar. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 23, 382–387. http://0-search.ebscohost.com.library.ualr.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=epref&AN=IJTLHE.BC.CHB.VANDER.CGEPTP&site=ehost-live&scope=site

Wiggins, G. (1998). Educative assessment: Designing assessments to inform and improve student performance. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Williams, R. (2006). Theorizing visual intelligence: Practices, development and methodologies for visual communication. In Hope, D. (Ed.) Visual Communication: perception, rhetorics and technologies. RIT Carey Press (pp. Xx – xx).

Winkelmes, M.-A. (2013). Transparency in teaching: Faculty share data and improve students’ learning. Liberal Education 99 (2). https://www.aacu.org/publications-research/periodicals/transparency-teaching-faculty-share-data-and-improve-students

Winkelmes, M.-A., Bernacki, M., Butler, J., Zochowski, M., Golanics, J., & Weavil, K. H. (2016). A teaching intervention that increases underserved college students’ success. Peer Review, 18 (1/2), 31–36. http://0-search.ebscohost.com.library.ualr.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=eue&AN=116776213&site=eds-live&scope=site

No comments yet.