Abstract

As patient and medication complexity grows, the demand for pharmacists with enhanced emotional intelligence, empathy, and resilience increases. While topics like healthcare communications and pharmacy ethics are routinely taught in the doctoral curriculum, there appears to be a gap in directly assessing emotional intelligence and its associated themes as they relate to professional identity formation. Dedicated learning time in the curriculum is necessary for students to consider themselves as professionals in these types of emotional spaces. Therefore, we created a new elective course in our Doctor of Pharmacy curriculum aimed specifically at these emotional intelligence and awareness. Ultimately, the goal of this course and content was to assist student pharmacists in merging individual growth with professional competency during the third-year curriculum. The rationale, design, implementation, assessment methods, and predicted changes for future course iterations are discussed here. Including emotional intelligence as a didactic and practical curricular topic is likely to impact future pharmacists in their abilities to delivery patient-centered care and participate in healthy and resilient professional careers.

Emotional intelligence is the ability to name and manage one’s own emotions and the emotions of others.1 It is a personality dimension that is becoming increasingly recognized for its importance in effective patient-centered care and its ties with mindfulness. The ability to demonstrate emotional intelligence can be considered a core component of professional identity formation, and one that can be enhanced through focused education and assessment.2

Healthcare professionals with higher levels of emotional intelligence are more likely to realize successful work-life balance, are better equipped to avoid burnout, and are more likely to become professional leaders.3 In addition, we hypothesized that given humanity’s own innate defense mechanisms, lack of emotional intelligence can lead to avoidance of fear-based engagement. In the pharmacy setting, both internal barriers (e.g., stigma projection) and external barriers (e.g., time priorities) highlight potential for patient discrimination.4 Self-stigma can also result from over-exposure to stigma in the workplace, potentially leading to decreased self-help and poor treatment outcomes. This can cause a downstream effect when it comes to establishing successful, non-discriminatory provider-patient relationships and/or may inhibit a provider from seeking self-help.

Therefore, we offered a unique elective course to third-year doctoral pharmacy (PharmD) students titled, “Bedside, Betterment, and Burnout: The Emotionally Aware Pharmacist.” This three-credit course addressed emotional intelligence in the professional setting, reviewed mindfulness as a means of practicing emotional intelligence, and discussed related themes. The course was built with attention to self and instructor assessment of topics that interweave with the all-encompassing umbrella phrase, “emotional awareness.”

Course Design Rationale

Emotional intelligence carries great significance in healthcare and healthcare education, affecting both patient safety and team dynamics. Codier and Codier illustrated the impact of emotional intelligence on team dynamics, describing emotional intelligence capacity, effective communication, and information transfer as keys to patient safety.5 Further, increased clinician emotional intelligence likely improves care and increases patient safety.5

Therefore, if emotional intelligence is taught as an ability which can be learned and modified, it may be used as a tool to improve clinician-patient relationships through non-discriminatory approaches and enhanced patient understanding.6 Beyond the patient relationship, improving capacity for emotional intelligence can enhance social interactions among professional peers. Relationships with patients and other healthcare professionals benefit from continued emotional intelligence development and awareness, thus providing an impetus for its role in pharmacy or healthcare-focused curricula.7

In this elective course, students were made aware of emotional intelligence, worked on activities directly related to improving emotional intelligence, and began a journey in self-development with goals of ultimately both benefitting patients and improving one’s own quality of life. The significance of emotional intelligence and its subsequent impact needs to be taught to both students and existing practitioners to improve the health and outcomes of patients and self.

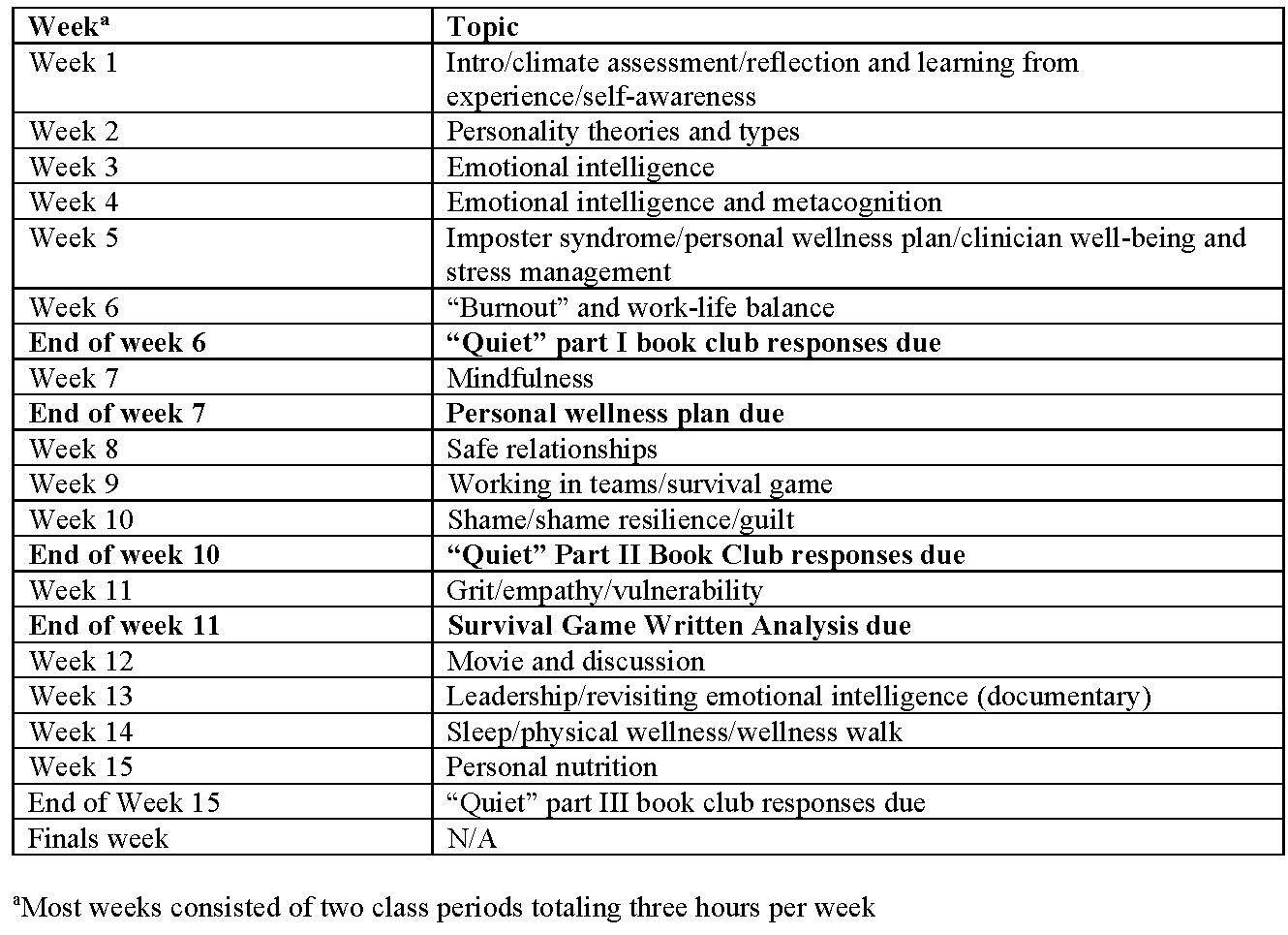

As our students were in the third year of a four-year professional program, this course was designed to address emotional intelligence in a broader context, focusing on both development of self and clinical interaction. Therefore, we chose to use the phrase “emotional awareness” to encompass the learning, development, practice, and reflection of skills including, but not limited to, emotional intelligence, imposter syndrome, mindfulness, shame, guilt, vulnerability, resilience, grit, empathy, wellness, and nutrition. A complete outline of course topics can be found in table 1. In this course, while we chose not to use the term, “soft skills,” we supported the use of “humanistic” or “intrapersonal skills,” sensing that these had more focused meanings. Ultimately, the goal of the course and content was to assist student pharmacists in merging individual growth with professional competency during the third-year curriculum.

Other works have described this type of content as “professional formation,” which focuses on service engagement, cyclic reflection and reiteration of experience, growth in self and field knowledge, and attention to one’s own inner and outer actions.8 We modeled this course on the pillars of weekly reflection, shared experiences, use of multiple tools to enhance field growth and knowledge, and course materials that best supported these actions. While this course offering did not have a service component, students in our curriculum actively participated in concurrent community service and introductory pharmacy practice experience hours.

Course Structure and Assessment

Weekly topics, presentations, and discussions were scheduled around professional identity formation, with the heart of the course focused on fostering emotional awareness. The course was heavily structured on application-based objectives and formative assessment, such as low-stakes discussion board postings, concept checks, and self-assessment. Course objectives and corresponding assessments are listed in table 2. Each week of the 15-week course was split into two class sessions, totaling three hours of weekly instruction.

As the course was rooted in the student’s ability to participate in discussions and activities, and a main theme was welcoming all personalities and confidence levels, methods in which students were awarded participation points varied. During the first of two weekly sessions, students were prompted for a silent journal entry during the initial five minutes of class. Simply having the journal in class and creating a written response were all that were necessary for that day’s participation point. The journal was not read or collected, so students were free to write at will. The point of the activity was to begin engaging students in the day’s topic.

To receive participation points during the second weekly class session, students were given two notecards with their names on them. During class, they had to participate in discussion or activities at least twice. Each time they spoke in class, they discarded a name card into a basket. Both cards had to be discarded for that day’s participation point to be awarded. Over time, this second activity was removed as all students naturally spoke up multiple times during class.

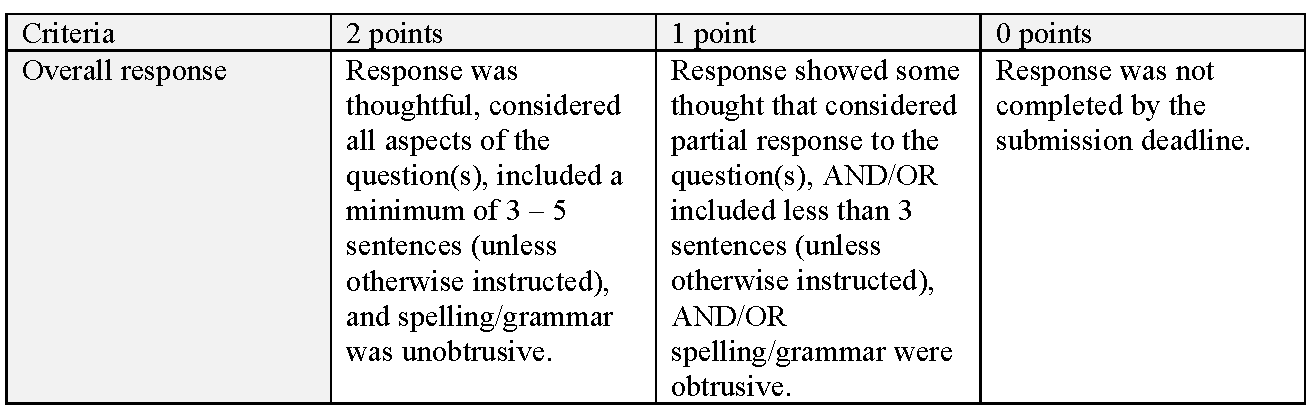

The main weekly assignment that allowed for free-form topic exploration was the online discussion board. This composed of 25% of the total course grade and was based upon a pre-determined rubric for response quality. The grading rubric, as depicted in Table 2, was short and included assessment of thoughtfulness, length/structure, and spelling/grammar. Here, students were given a weekly prompt based on in-class discussions, but the prompt allowed students to respond creatively (e.g., “Post a piece of original artwork or share a link to a favorite artwork that demonstrates healthcare-related burnout,” or “Am I a good person because of what I do (work hard/serve others)? Is it enough that we are just as we are? Whose expectations am I trying to meet?”).

Traditional examinations were avoided in this course, as they were not consistent with course objectives. Therefore, in lieu of summative examinations, once per week students were asked to complete an auto-graded online “check for understanding.” These were low-stakes multiple choice or fill-in assessments that corresponded to the day’s objectives, and essentially served to rapidly gauge student understanding.

Students were also assigned three non-repeating assignments. The first assignment was a longitudinal personal wellness plan encompassing both an in-class activity and an external written narrative.9 Students were provided with an in-class overall assessment that asked them to consider nine dimensions of personal wellness, encompassing considerations such as academic, emotional, occupational, and financial wellness. The planning document lead students through eight reflective steps to designing a longitudinal wellness plan, which included self-reflection and the creation of specific, measurable, and timely goals. Students were then assigned a written summary narrative, which included items from the planning document. This assignment’s assessment rubric is shown in Table 3.

Next, students participated in a team-based National Aeronautics and Space Administration survival game.10 Here, students completed a two-hour in-class activity, in which they ranked survival items by importance under the context that they were stranded on the moon. Group consensus was necessary to rank an item. Following the activity, the answer key was revealed and compared to the group’s ranking. A follow-up written assignment asked students to consider the group dynamics by describing the team’s approach to the activity, group methodology, group functionality, and individual assessment of participation. This assignment was worth 15% of the overall course grade, and its assessment rubric is show in Table 4.

Finally, three written reflective exercises were linked to a book read independently throughout the semester. The intent of the three book reflections was to mirror a longitudinal book club. During the first offering of this course, the chosen book was Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking, by Susan Cain.11 Each book reflection was a targeted five-question assignment on the first, second, and third portions of the book, worth five percent of the total grade (three reflections totaling 15%). Book selection is likely to change with each course iteration and/or based on student feedback.

Throughout the course, students participated in several in-class, non-graded reflective activities and validated surveys that contributed to an overall understanding and reflection of self and identity. Among these tools were items such as a comparable free version of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, textbook-based self-assessments, samples of Compassion Fatigue Self-Assessments, and others.12,13,14 Discussions followed as to how one’s own responses to these activities influenced roles in the personal and professional setting. These discussions included case and scenario-based thought experiments, challenge questions, and small group work.

Overall, it was determined that future iterations of the course can likely do away with this “checks for understanding,” as these items appeared not to lend themselves to any substantial gains except possible grade inflation. The grading rubrics that we used for written assignments were designed to be minimalistic to encourage a more free-form approach to a response. As this course was intentionally created for emotional awareness exploration and development, the instructors felt that providing students less structured opportunities for grading was important. Lastly, we determined that pre- and post-assessment of emotional awareness-type surveys would be key in future course offerings.

The Bigger Picture

As the pharmacy profession makes progress towards its goal of having more pharmacy practitioners delivering direct patient care, emotional intelligence and awareness will be essential skills for patient engagement. With the goal of embedding pharmacists into physician practices, the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy, in partnership with the American Medical Association, has developed a program for physicians to increase the numbers of pharmacists working directly within their practices to improve patient care.15 In a fee-for-service healthcare system, however, pharmacists will be working as members of the healthcare team in fast-paced environments, and they will often be engaging patients with illnesses at risk for discrimination (e.g., mental illness, obesity, human immunodeficiency virus, cancer).4 Primary care practices (and community pharmacies) are care settings where patients with these illnesses frequently receive treatment.

In a recent survey, primary care physician respondents reported diagnoses of substance use, major depressive and anxiety disorders in up to one-third of all new patients.16 Because pharmacist practitioners must address all medication related problems, their skill at engaging patients with illnesses of discrimination will benefit from a firm foundation in emotional intelligence. Further, since these same illnesses represent obstacles to pursuing care for pharmacists who experience them, emotional intelligence will be a skill that could allow them to navigate the fear and shame related to seeking help for those illnesses.17

Conclusion

This first offering of the PharmD student elective on emotional intelligence and awareness was delivered in accordance with its intent. Future iterations of this course will likely include objective structured clinical examinations focused on emotional intelligence, activities designed to teach agitation de-escalation techniques, and measurement of course impact using validated surveys. Ideally, this course will be offered repeatedly and to increasing numbers of students in the PharmD curriculum. Extension of course delivery to other healthcare professions may also be considered. Inclusion of emotional intelligence as a didactic and practical topic in the PharmD curriculum, especially via this type of course with its core message of professional identity formation, is likely to impact future pharmacists in their abilities to delivery patient-centered care and participate in healthy and resilient professional careers.

Authors

Kimberly Pesaturo, PharmD, BCPS is a Clinical Associate Professor and Assistant Dean for Assessment and Accreditation for the College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences (WNEU). She received her Doctor of Pharmacy degree from the University of Rhode Island, and completed two post-graduate pharmacy residencies, first at Saint Joseph Health in Lexington, KY, and then at UK HealthCare in Lexington, KY, specializing in pediatrics. Dr. Pesaturo previously held a faculty appointment with MCPHS University’s College of Pharmacy, an adjunct appointment with MCPHS University’s School of Professional Studies, and an adjunct appoint with the Higher Education Consortium of Central Massachusetts. Since joining WNE in 2020, she has continued her research in learner-centered assessment and was a speaker in WNE’s inaugural TEDx Conference.

Kimberly Pesaturo, PharmD, BCPS is a Clinical Associate Professor and Assistant Dean for Assessment and Accreditation for the College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences (WNEU). She received her Doctor of Pharmacy degree from the University of Rhode Island, and completed two post-graduate pharmacy residencies, first at Saint Joseph Health in Lexington, KY, and then at UK HealthCare in Lexington, KY, specializing in pediatrics. Dr. Pesaturo previously held a faculty appointment with MCPHS University’s College of Pharmacy, an adjunct appointment with MCPHS University’s School of Professional Studies, and an adjunct appoint with the Higher Education Consortium of Central Massachusetts. Since joining WNE in 2020, she has continued her research in learner-centered assessment and was a speaker in WNE’s inaugural TEDx Conference.

Melissa Mattison graduated from the University of Rhode Island with a BS in pharmacy then returned to school at the University of Florida for her PharmD degree. Prior to joining the faculty at Western New England University, Dr. Mattison worked in community pharmacy for Walgreens in Connecticut, Louisiana, and Massachusetts, where she precepted students and trained new graduate pharmacists. Dr. Mattison is currently the Assistant Dean of Experiential Affairs overseeing interprofessional education and community outreach as well as experiential education. She is a Clinical Associate Professor of Community Care and a certified diabetes care and education specialist (CDCES), specializing in obesity and weight loss serving as the clinical director of the Community Patient Care Center on campus. Dr. Mattison’s areas of interest include health and wellness, motivational interviewing, interprofessional education, self-care, and disease prevention. Dr. Mattison engages learners in the classroom, teaching Professional Development, Self-Care Therapeutics, Professional Pharmacy Practice lab, immunization training, and an interprofessional education elective. Additionally, Dr. Mattison is the preceptor for the community care resident on campus. Dr. Mattison was recognized as Professor of the Year in 2013 and 2020 and received the Excellence in Scholarship award in 2015.

Melissa Mattison graduated from the University of Rhode Island with a BS in pharmacy then returned to school at the University of Florida for her PharmD degree. Prior to joining the faculty at Western New England University, Dr. Mattison worked in community pharmacy for Walgreens in Connecticut, Louisiana, and Massachusetts, where she precepted students and trained new graduate pharmacists. Dr. Mattison is currently the Assistant Dean of Experiential Affairs overseeing interprofessional education and community outreach as well as experiential education. She is a Clinical Associate Professor of Community Care and a certified diabetes care and education specialist (CDCES), specializing in obesity and weight loss serving as the clinical director of the Community Patient Care Center on campus. Dr. Mattison’s areas of interest include health and wellness, motivational interviewing, interprofessional education, self-care, and disease prevention. Dr. Mattison engages learners in the classroom, teaching Professional Development, Self-Care Therapeutics, Professional Pharmacy Practice lab, immunization training, and an interprofessional education elective. Additionally, Dr. Mattison is the preceptor for the community care resident on campus. Dr. Mattison was recognized as Professor of the Year in 2013 and 2020 and received the Excellence in Scholarship award in 2015.

Charles Caley received his BS Pharm and Doctor of Pharmacy degrees from the University of Rhode Island. Prior to pursuing his PharmD, he practiced community pharmacy on the island of Martha’s Vineyard. Following his PharmD, he completed a two-year specialty residency in psychiatric pharmacotherapy. Year one was completed at the Institute of Mental Health in Cranston, Rhode Island, and year two at Eastern State Hospital in Medical Lake, Washington. He has been board certified in psychiatric pharmacy since 1996. Among other areas of research and scholarship, Dr. Caley is interested in strengthening the connections between students and patients through self-discovery and emotional awareness.

Charles Caley received his BS Pharm and Doctor of Pharmacy degrees from the University of Rhode Island. Prior to pursuing his PharmD, he practiced community pharmacy on the island of Martha’s Vineyard. Following his PharmD, he completed a two-year specialty residency in psychiatric pharmacotherapy. Year one was completed at the Institute of Mental Health in Cranston, Rhode Island, and year two at Eastern State Hospital in Medical Lake, Washington. He has been board certified in psychiatric pharmacy since 1996. Among other areas of research and scholarship, Dr. Caley is interested in strengthening the connections between students and patients through self-discovery and emotional awareness.

References

- Institute for Health and Human Potential. The meaning of emotional intelligence. https://www.ihhp.com/meaning-of-emotional-intelligence/. Accessed Feb 14, 2024.

- Goleman D. What makes a leader? Harvard Business Review.1998;93 – 102.

- Lane T. Emotional intelligence. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2019;101(1):1.

- Calogero S, Caley C. Supporting patients with mental illness: deconstructing barriers to community pharmacy access. J Amer Pharm Assoc. 2017;57:249 – 255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.japh.2016.12.066. Accessed Feb 14, 2024.

- Codier E, Codier DD. Could emotional intelligence make patients safer? Am J Nurs. 2017;117(7):58-62.

- Johnson DR. Emotional intelligence as a crucial component to medical education. Int J Med Educ. 2015 Dec 6;6:179-83. https://www.ijme.net/archive/6/emotional-intelligence/. Accessed Feb 14, 2024.

- Butler L, Park S, Vyas D, Cole JD, Haney JS, Mars JC, Williams E. Evidence and strategies for inclusion of emotional intelligence in pharmacy education. Amer J Pharm Educ 2021; 86(5):Article 8674.

- Rabow MW, Remen RN, Parmelee DX, Inui TS. Professional formation: extending medicine’s lineage of service into the next century. Acad Med. 2010;85(2):310 – 317. https://journals.lww.com/academicmedicine/Fulltext/2010/02000/Professional_Formation__Extending_Medicine_s.33.aspx. Accessed Feb 14, 2024.

- University of Arizona. Pathway to personal wellness. https://health.arizona.edu/sites/default/files/Pathways_to_Wellness_Personal_Wellness_Plan_Worksheet_8-28-20_0.pdf. Accessed Feb 14, 2024.

- NASA and Jamestown Education Module. Exploration then and now. https://www.nasa.gov/pdf/166504main_Survival.pdf. Accessed Feb 14, 2024.

- Cain S. Quiet: the power of introverts in a world that can’t stop talking. 2nd edition. New York: Broadway Books; 2013.

- The Myers Briggs Foundation. Take the MBTI inventory. https://www.myersbriggs.org/my-mbti-personality-type/take-the-mbti-instrument/. Accessed Feb 14, 2024.

- Tipton D. Self-awareness for healthcare professionals. 1st edition. Washington, DC: American Pharmacists Association; 2021.

- Compassion fatigue self-test for practitioners. https://www.mtleague.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/CompassionFatigueSelfTestforPractitioners.pdf. Accessed Feb 14, 2024.

- Choe HM, Standiford CJ, Brown MT. Embedding pharmacists into the practice: collaborate with pharmacists to improve patient outcomes. AMA STEPS Forward. 2017. https://edhub.ama-assn.org/steps-forward/module/2702554. Accessed Feb 14, 2024.

- University of Michigan Behavioral Health Workforce Research Center. Behavioral Health Service Provision by Primary Care Physicians. Ann Arbor, MI: UMSPH; 2019. https://www.behavioralhealthworkforce.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Y4-P10-BH-Capacityof-PC-Phys_Full.pdf. Last accessed Feb 14, 2024.

- Knaak S, Mantler E, Szeto A. Mental illness-related stigma in healthcare: barriers to access and care and evidence-based solutions. Healthc Manage Forum. 2017;30:111 – 116. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5347358/. Last accessed Feb 14, 2024.

Appendix

Table 1. Course Outline and assignment schedule

Table 2. Course Objectives

Figure 1. Discussion board response assessment rubric

Figure 2. Longitudinal wellness plan written analysis assessment rubric

Figure 3. Survival game written analysis assessment rubric

No comments yet.