“In the problem is the solution” – J. Krishnamurti

Abstract

Pedagogical love is the genuine care and empathy expressed by a teacher towards a student’s learning experience and growth. This concept became starkly relevant when we transitioned abruptly to an online mode of instruction. During this period, the immense power of the assessment revealed itself while the significance of the grade dimmed somewhat. More specifically, formative assessments took center stage allowing us to fully experience assessment for learning. Lessons learned during the spring informed an instructional design that now emphasizes pedagogical love through communication, conceptual clarity, and congruence. The design needs to be fluid as we journey through this learning curve.

Key Words: Pedagogical love, mastery, formative assessment, communication, conceptual clarity, congruence.

Introduction

The importance of love and kindness in pedagogy has gained momentum in the new millennium (Cho, 2005; Loreman, 2011; Maatta and Uusiautti, 2012; Akkaraju, Broughton, Atamturktur, and Frazer, 2018; Wilkinson & Kaukko, 2020). Care in pedagogy was classified by Valenzuela (Valenzuela, 1999) as aesthetic care and authentic care. Aesthetic care is superficial and limited to caring about student performance and disposition. Authentic care is the deeper version that emphasizes a reciprocal relationship between a student and teacher in which the student feels cherished.

When we shifted abruptly to distance learning in the midst of the global pandemic that hit New York City quite heavily, the transition from aesthetic care to authentic care was inevitable for many of us. Authentic care took on an almost urgent, yet enduring place in my virtual classroom. For me, pedagogical love was stronger than ever and I was able to find newer and more engaging ways to demonstrate it. The students reciprocated by staying in touch with me constantly, challenging themselves, allowing themselves to be vulnerable, finding strength, and rising to the occasion. The pedagogical vocabulary in my head began to shift from words like scores, deadlines, and grades to assessment, learning, and growth. Minimizing the role of grading and maximizing the role of the formative assessment helps us to emphasize feedback, proficiency, and mastery (Sackstein, 2015).

The formative assessment is a very powerful way to engage students deeply in the learning process (Black & Wiliam, 1998; Moss & Brookhart, 2019). In my own experience, I have used formative assessments in conjunction with the flipped classroom model with very encouraging results (Akkaraju, 2016; Akkaraju, 2018). In gateway science courses, the flipped format is successful when accompanied by regular nudges via text messaging, a practice that I have found to be highly effective (Sherr, Akkaraju, and Atamturktur, 2019). Having embedded both these practices in my regular face to face courses, transitioning to the online environment was somewhat seamless.

Yet, a couple of major challenges had to be addressed: (1) How to deliver content in a a way that introduces desirable difficulties thereby promoting a deeper engagement with the material? (2) How to administer summative assessments in a way that is both valid (given the absence of proctoring) and meaningful to the student? I was happy to discover that major challenges when examined closely, present major opportunities. I addressed the former by creating mini-lecture videos that included interactive questions at various points. I addressed the latter by introducing the oral exam for both benchmark and summative assessments, something that I have always wanted to attempt. Both these strategies took an enormous amount of effort that paid off handsomely by the end of the semester. The students responded with enthusiasm, which was also reflected in their outstanding performance.

The lessons that I learned from the spring helped me to re-imagine my biology courses (Human Anatomy & Physiology I and II) to be taught in an asynchronous mode combined with a 1-hour weekly synchronous recitation session. I allowed pedagogical love to drive major aspects of my instructional design such as communication, conceptual clarity, and congruence. In this article, I will describe my instructional design and how it is continuously being adapted to suit student needs.

Instructional Design

Communication

The purpose, mode, frequency, and tenor of communication with the students had to be carefully considered because this is a crucial aspect of the instructional design (Pritts, 2020). A thoughtful communication strategy is essential to meet student needs, especially when dealing with an asynchronous method of transmission. Prior to the transition, I had been using Remind, the mobile messaging application to keep in touch with the students by sending them updates, reminders, and gentle nudges with excellent results (Sherr, Akkaraju, & Atamturktur 2019). My decision to use a mobile messaging application turned out be a lifesaver during the pandemic. The purpose of using this application is to make the student feel cared for and to gently nudge them into completing all their assignments in a timely fashion. Combined with the use of laughter, smile, thumbs up, and other positive emojis, text messaging allows for a more relaxed and friendly communication with the students.

How is it working? The students were unanimous in their liking of Remind. They also agreed that they did not once feel left out in the cold during the first week of classes and that they were able to gain access to me. However, the volume of messages that I received during the first week of the semester was somewhat overwhelming.

Intervention. I realized that I could learn from the volume of messages because these messages are indicators that alert me when something is not working. The goal therefore is to reduce the number of incoming messages while still keeping communication lines open. I streamlined the messages by grouping them into a few categories. This allows me to tweak the design in a way that will help smoothen out the learning experience and reduce the noise (Table 1).

Using messages as indicators to modify instructional design

| Issue raised in text messages | Examples | How do I address this? |

| Navigation | I cannot find the lab homework | Make a flow chart to help students navigate the course easily. |

| Troubleshooting | This link is broken There appears to be a problem with this question | Create a routine checklist for myself to use whenever new homework is assigned. This will minimize the need for troubleshooting later on (Gawande, 2010). |

| Clarification | Am I allowed to do this quiz again? | Include brief, clear guidelines along with each task |

| Grades | Why did I get this grade? | Be kind. Be transparent. Give feedback. Communicate expectations. |

| Personal issues | I need to get surgery There’s been a death in my family | Be kind. Be supportive. |

Conceptual Clarity

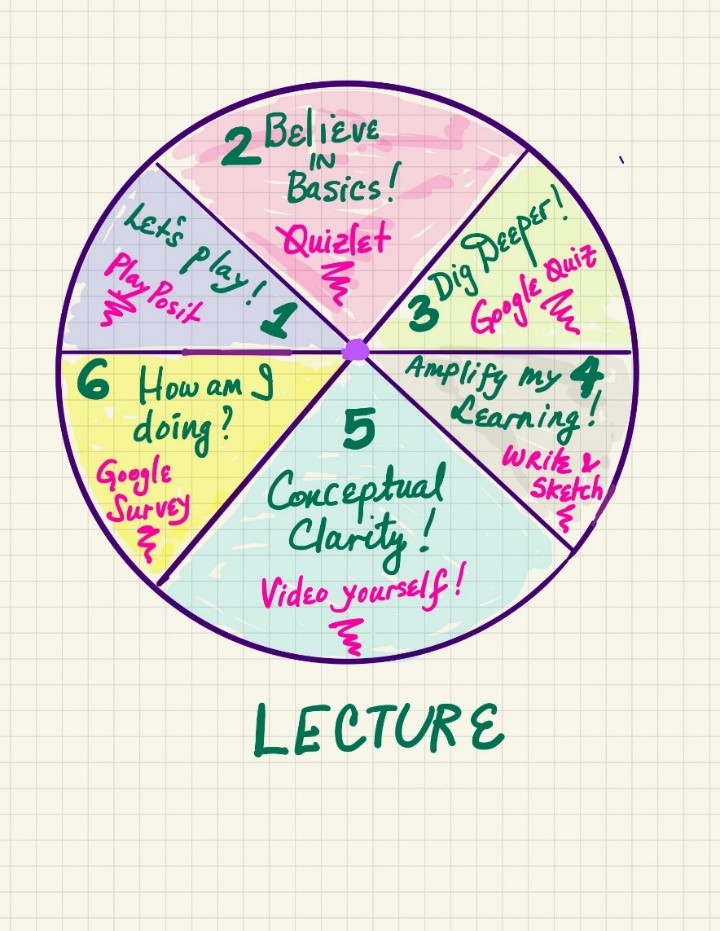

A major learning outcome of my instructional design is that the student will be able to demonstrate conceptual clarity on a weekly basis. In order to achieve this, they need to undergo a series of scaffolded learning experiences that would help them to engage with the material, master the basics, dig deeper into the concept, amplify learning by sketching and writing by hand. As a final step in the learning process, the student demonstrates conceptual clarity by recording a video explanation of the major concepts learned that week (Figure 1)

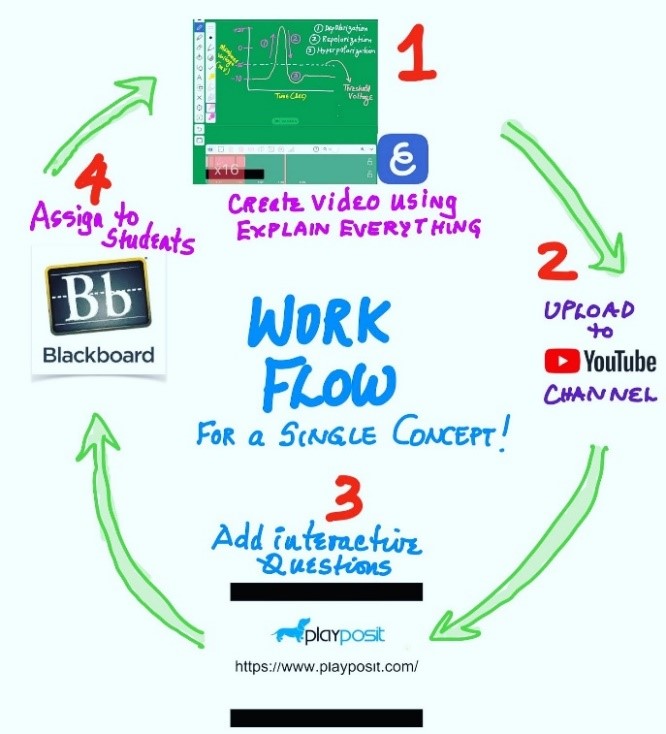

All these learning opportunities are designed as desirable difficulties, which significantly deepen engagement and help to build crucial study skills (Brown, Roediger, and McDaniel, 2014; Akkaraju, 2018). A desirable difficulty is supposed to be challenging enough to be interesting but not too challenging that it discourages the learner. To this end, I used a variety of educational technology platforms such as PlayPosit, Quizlet, and Google Quiz to streamline content and customize the learning experience. In order to practice intentional content and provide a learning experience that would closely resemble being in a classroom, I created a series of mini videos using a platform called Explain Everything. The journey from here to the PlayPosit experience involves many steps in between (Figure 2).

The ultimate test for conceptual clarity would be to see if the student is able to explain concepts and think like a physiologist when asked questions in an oral exam setting. I tried this type of assessment for both benchmark (monthly lecture exams) and summative (cumulative final lecture exam) assessments in the spring when we transitioned to a fully online mode. Majority of the students (80%) met or exceeded the benchmark for the spring semester and all the students (100%) agree to the statement that the oral exam was a powerful learning experience. In my current instructional design, the weekly video explanation with the tag line Conceptual Clarity (see Figure 1) is a way to train students for the benchmark and summative assessments.

How is it working? Results from week one indicate that almost all students are enjoying their learning experience. A few students in each course did exceptional work in terms of their video explanations, which I was able to showcase to their class using the showcase feature in Dropbox. However, there were some challenges:

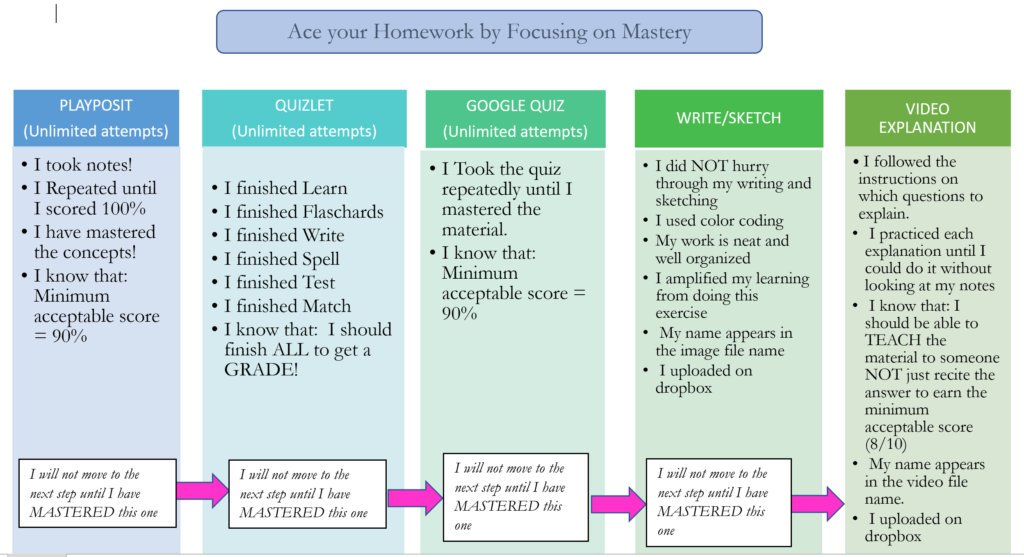

- About half the students, while showing enthusiasm to attempt the PlayPosit, Quizlet, and Google Quizzes, did not approach these assignments with mastery in mind.

- Some of them also did not realize that they had unlimited attempts on quizzes to help them master the material.

- Students appeared to be in a great hurry to complete their homework and press submit without checking if they had actually hit the benchmark.

- A few began the work and gave up too easily.

Intervention. I realized that I had not given clear guidelines to the students on how to approach their homework. They were given a roadmap that was missing road signs and milestones. Navigating their weekly homework is a complex process and any complex process needs a checklist (Gawande, 2010). I developed a detailed checklist with road signs and milestones that would help them better understand the expectation for each formative assessment (Figure 3).

Congruence

If an instructional design is to be effective, then it must be congruent. This means the formative assessments must build upon each other and gently lead the student towards the summative assessment. Students are guided by a weekly checklist (Figure 3) that shows them how to approach their homework and what is expected of them at each stage. Students are also made aware that there is a high degree of congruence from stages one through five and to skip a stage would be detrimental to their learning experience.

How is it working? About 50% of the students understood the importance of approaching their homework in stages without skipping around. They mentioned that they enjoyed how their conceptual understanding improved with each passing stage. The other half was skipping around randomly even though the homework is arranged sequentially in their Bb weekly homework folder.

Intervention. I realized that they were not taking advantage of the congruence aspect of the instructional design because they were missing the road signs. Clearly, they needed a checklist accompanied by clear signage, which I created and shared with both classes (Figure 3).

Conclusion

I have learned a great deal during these first two weeks of classes. I now realize that in order for this instructional design to work, there needs to be a heightened level of awareness to pick up on early signs of students struggling so that there is an opportunity to act swiftly and decisively in favor of the student learning experience. The best way to practice awareness, stage interventions, and examine the results of these interventions is to fully commit to the habit of reflective practice. In other words, practice assessment as an act of love (Torres, 2019). This is of vital importance because we care that our students are happy in a learning environment that supports mastery.

Author(s)

Shylaja Akkaraju, Professor, Department of Biological Sciences, Bronx Community College, CUNY

References

Akkaraju, S. (2016). The Role of Flipped Learning in Managing the Cognitive Load of a Threshold Concept in Physiology. Journal of Effective Teaching, 16(3), 28-43.

Akkaraju, S. (2018). Handwriting to Learn: Embedding a crucial study skill in a gateway science course. Journal of Effective Teaching in Higher Education, Vol 1(1), 55-72.

Akkaraju, S., Atamturktur, S., Broughton, L. and Frazer, T. (2019), Ensuring Student Success: Using Formative Assessment as the Key to Communication and Compassion Among Faculty, Students, and Staff. New Directions for Community Colleges, 2019: 71-79. doi:10.1002/cc.20358

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (1998). Assessment and classroom learning, Assessment in Education, 5(1), 7-14.

Brown, P.C., Roediger, H.L. and McDaniel, M.A. (2014). Make it stick: The science of successful learning, 336p, Belknap Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Cho, D. (2005). Lessons of Love: Psychoanalysis and Teacher/Student Love, Educational Theory 55 (1), 79-95.

Gawande, A. (2010). The Checklist Manifesto: How to get things right, New York: Metropolitan Books.

Loreman, T. (2011). Love as Pedagogy, Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Maatta, K. & Uusiautti, S. (2012). Pedagogical authority and pedagogical love: Connected or incompatible? International Journal of Whole Schooling, Vol 8(1), 21-39.

Moss, C.M. & Brookhart, S.M. (2009). Advancing formative assessment in every classroom: A guide for instructional leaders. Alexandria, VA: ASCD

Pritts, N. (2020). Using announcements to give narrative shape to your online course. Faculty Focus, June 1, 2020.

Sackstein, S. (2015). Hacking Assessment: 10 ways to go gradeless. Times 10 Publications.

Sherr, G., Akkaraju, S., & Atamturktur, S. (2019). Nudging Students to Succeed in a Flipped Format Gateway Biology Course: Vol. 2 (2) (pp. 57–69).

Torres, C. (2019). Assessment as an act of Love, ASCD Education Update, February 2019, Vol 61(2)

Valenzuela, A. (1999). Subtractive schooling: U. S.-Mexican youth and the politics of caring. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Wilkinson, J. & Kaukko, M. (2020) Educational leading as pedagogical love: the case for refugee education, International Journal of Leadership in Education, 23:1, 70-85, DOI: 10.1080/13603124.2019.1629492

This wonderful, innovative article is even more special because it comes from a teaching scientist. Too many times, colleagues working outside of the humanities complain that they cannot maintain rigor without old-fashioned models of assessment. Thank you.