A New Approach to Assessing Teaching/Learning

To satisfy various stakeholders, including their institution’s administrators, faculty assess the effectiveness of their teaching (Haras, et. al, 2017). End-of-course student evaluations are still the most widely used method to assess teaching (Lawrence, 2018). Increasingly, however, research evidence shows that student bias, such as expected grade, gender, age, race, and attractiveness of the teacher all have significant impact on faculty ratings (Boring, Ottoboni & Stark, 2016; Nilsen, 2012). Student assessments of teaching focus on teacher personality characteristics and teaching or presentation style, and not on how effective the teacher was to promote student learning (Nilsen, 2012). Student end-of-course evaluations rate student satisfaction, like consumers rating a product, with the instructor as a person, and not necessarily their teaching abilities. Still, many higher education institutions use student evaluations for important decisions such as salary increases, tenure decisions, promotions and even job retention, especially for new or adjunct faculty (Strobe, 2016). Many students reward teachers who give them high grades with high ratings and give teachers lower ratings if students receive lower grades than what they expected or wanted (Nilsen, 2012; Strobe, 2016). Because faculty need to maintain good or outstanding course evaluations, faculty have reduced standards and the amount of work required (Strobe, 2016). The weight that student course evaluations and the pressure to receive excellent evaluations has paradoxically led to a culture of less rigorous education (Lawrence, 2018.)

To demonstrate their teaching effectiveness, teachers must use evidence beyond student course evaluations. Collecting data to evaluate teaching should also be used to foster improvements in teaching as opposed to being punitive. The purpose of this article is to describe a data collection method that also suggests ways to improve teaching.

Learning-Centered Teaching Is Effective Teaching

The traditional model of lecture-based higher education, even with the use of beautiful presentation slides, detailed learning guides, and sophisticated technology does not lead to significant student learning gains, long-term retention, nor the ability for students to use what they’ve learned in new situations (Felder & Brent 2016; Weimer, 2013). The inadequacies of the traditional educational methods became even more pronounced in the past two years when students were removed from the classroom and their instructors and forced to learn remotely. At the same time, faculty in higher education are facing increased pressure from varied stakeholders including students, employers, legislators, policy makers, administrators, and accrediting bodies to teach effectively (Haras,et .al., 2017). Not surprisingly, faculty are looking for more successful ways to teach.

Effective teaching practices integrate professional expertise with the best available evidence-based research (Felder & Brent 2016; Weimer, 2013). The American Council on Education (2018) characterizes effective teaching as using a variety of active learning techniques with students working together and not competing, frequent assessment of learning, and helping students to succeed. Increasing empirical research indicates that learning-centered teaching leads to better results; this approach uses all these characteristics of effective teaching recommended by the American Council on Education (Bok, 2015; Suskie, 2014; Weimer, 2013). Learning-centered teaching is an evidence-based best educational practice that has been used with all disciplines, levels of students, and size of classes (Weimer, 2013).

Consequently, many faculty are striving to incorporate more learning-centered teaching approaches. These approaches focus on the learning process and student learning outcomes. Learning-centered teaching is not a single teaching method; it covers a variety of evidence-based techniques and pedagogies that help students to learn. Instead of the teacher focusing on preparing lectures or detailed notes to disseminate information, teachers become facilitators to help students learn and succeed. When teachers use learning-centered teaching, students acquire deep and lasting learning that they can use to solve problems in real world situations (Weimer, 2013).

Weimer’s (2002, 2013) groundbreaking model discusses why faculty must change five broad educational practices to employ learner-centered teaching. These practices are: 1) Role of the instructor, 2) Developing student responsibility for learning, 3) Function of content, 4) Purposes and processes of student assessment, and 5) Balance of power. Blumberg (2019) built upon these five practices and refined Weimer’s (2003, 2013) model by calling it learning-centered teaching because of her focus on the learning process. She called Weimer’s practices “constructs.” Further, Blumberg (2019) operationally defined six essential actions within each construct that should be implemented to achieve learning-centered teaching. These essential actions are consistent with the extensive and current research on teaching and learning and apply to all types of teaching. Here are two actions within the role of the instructor construct: 1) using challenging, reasonable, and measurable learning outcomes that foster the acquisition of appropriate knowledge, skills, or values; 2) employing teaching learning methods and educational technologies that promote the achievement of student learning outcomes. Blumberg (2019) further differentiated the implementation of each of these actions according to four levels of increasing learning-centeredness that she called a) instructor-centered, b) minimally learning-centered, c) mostly learning-centered, and d) extensively learning-centered.

Assessing the Implementation of Learning-Centered Teaching

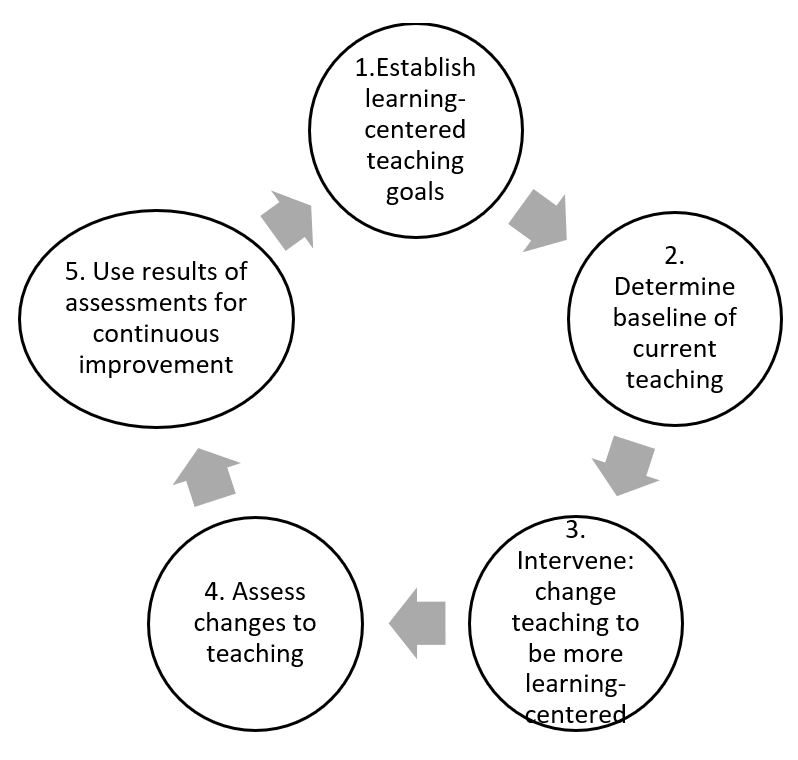

Suskie (2009) proposed a now popular assessment cycle that can be used to assess the use of learning-centered teaching, as shown in Figure 1. Establishing goals (step 1) prior to determining baselines (step 2) is a recommended assessment practice although this may seem counter intuitive and is not commonly practiced. These goals should come from teachers’ own reflections about their teaching or feedback from their students, peers, educational developers, or chair of their department. Goals can lead to better decision making about changes. These changes are called the intervention in this model (step 3). Because goal-specific data are collected to indicate whether the goal has been achieved, teachers can employ streamlined data collection (step 4). This makes the assessment task manageable and not overwhelming. Establishing goals and having a plan for how the data will be used increases the likelihood that the results will be used to make further improvements (Step 5). This is referred to as closing the assessment loop and is the most important reason to engage in assessment. These further changes or improvements based upon the results of the data can be an iterative process. Traditional evaluation forms or methods do not provide data to assess whether learning-centered teaching improvement goals have been met, since many of them do not assess these teaching practices.

(Modeled after Suskie, 2009)

Because rubrics effectively communicate expectations and easily measure the quality of performance, they are often used to assess student assignments. Using rubrics with distinct levels of performance, teachers judge products or behaviors using specific criteria. Rubrics are also valid tools to assess faculty performance. Unlike rubrics used for students, rubrics for teachers should not have pass and fail levels or even evaluative labels such as “needs improvement.” Instead, rubrics to evaluate the effectiveness of teaching practices can list strengths and weaknesses and potential areas for improvement of teaching.

Using her learning-centered teaching model, Blumberg (2019) created a descriptive rubric for the six actions for each of the five constructs. (See Table 1) The table yields thirty essential actions or criteria that can be evaluated for the implementation of learning-centered teaching. The consistent labels for the standards for the rubrics are the four increasing levels of implementation from instructor-centered to extensively learning-centered. The description of these levels is specific to the teaching characteristics for each action. The three levels of learning centered teaching on the rubrics also suggest ways of incrementally becoming more learning centered. Table 2 provides the rubric for an action within Role of the Instructor. Since teaching performance rubrics are used to identify many characteristics of the complex teaching process, they can have several definitions or descriptors at each level. And/or statements connect these quality descriptors. At the lower levels, faculty can demonstrate some; the highest level require demonstration of all of them. Faculty members select the specific characteristics that apply to their teaching. Unlike assessing teaching performance, having several characteristics or descriptors at each level is not a good assessment practice for students.

Blumberg’s (2019) rubrics can be used to assess the extent of learning-centered teaching through self- assessment, and/or in consultation with peers, faculty developers, or their chairs. They identify evidence to demonstrate the extent to which they use learning-centered teaching. Course syllabi often contain useful information to assess learning-centeredness by reviewing course policies and practices. All course artifacts developed by the instructor including lesson notes, class plans, or instructions for class activities and assignments also provide support for completing the rubrics to indicate the extent to which learning-centered teaching approaches have been implemented. Student artifacts such as their responses to assignments or work they completed in group activities in or out of class are commonly used to assess or support learning-centered teaching ratings. When teachers consider these diverse types of evidence, they are more likely to truthfully represent the extent of implementation of learning-center teaching. Without such evidence some faculty may be inclined to exaggerate their use of learning-centered teaching practices. Peers, educational developers, or chairs can corroborate self-assessments from the evidence that the individual provides.

The same rubrics should be used to gather baseline data (Step 2 of the assessment cycle) prior to the intervention and after the intervention (Step 4 of the assessment cycle). Faculty can choose to assess themselves on all thirty essential actions of the learning-centered teaching model or only those actions that relate to their teaching improvement goals. Based upon the rubric scores prior to the intervention, faculty may develop specific goals or aspirational rubric levels such as moving from instructor-centered to mostly learning-center teaching. The three learning-centered levels on the rubric offer suggestions for increasing the implementation of learning-centered teaching. Often changes in one action lead to improvement in learning-centered teaching in other actions. This is a good reason to assess all thirty actions pre-and-post intervention.

Faculty can report the range of their levels, the frequency of each level, their most common level, and the percentage of actions at each of the four levels. These descriptive statistics can be graphically shown as either clustered column charts or pie charts. Changes can be summarized in a table or bar graphs and dumbbell charts (Evergreen 2017). Since this is deliberately not an interval scale, faculty should not report means and standard deviations to summarize the data.

In addition, the data on the rubric scores can be used to create an individual SOAR (Strengths, Opportunities, Aspirations, and Results) analysis (Table 3). The SOAR analysis is a more positive-thinking technique that leverages strengths and opportunities to promote changes over the more commonly used SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) analysis (American Society of Quality, 2016). When people perform a SWOT analysis they tend to try to correct their weaknesses. Even when faculty try to correct their weaknesses they may not teach more effectively. In some cases the weaknesses are beyond their control. The SOAR summary can also document aspirations or how they want to change their teaching in the future in their annual evaluations or teaching portfolios. Table 3 provides a template for personal SOAR analysis of learning-centered teaching.

Once faculty have their results from the rubrics and SOAR analyses, they should include this information along with an explanation of this model, and adequate evidence or support for how the scores were determined on their annual performance reviews, teaching portfolios, and dossiers for promotion and tenure. Faculty should include supportive narratives and examples from the faculty member’s teaching and describe how teaching changed in enough detail so that others who are not familiar with the individual or the course will be able to determine how the evaluator arrived at the ratings both pre-intervention and post-intervention.

Summary and Conclusion

Administrators and accreditors expect faculty to assess the effectiveness of their teaching. Faculty may be perplexed to evaluate all aspects of their teaching and perhaps find this an overwhelming task. Using the assessment method described should make the evaluation of teaching less daunting for individual faculty members. With the use of this assessment method, the evaluation of teaching moves beyond just students’ opinions on course evaluation forms and becomes supported by evidence.

This article described a feasible method for faculty to evaluate their use of learning-centered teaching, an evidence-based, best practice teaching approach. The commonly accepted assessment loop is a foundation for this assessment method. Rubrics offer a convenient and consistent way to evaluate the complex teaching process and summarize the results in concise and meaningful ways for other people to understand the assessment. Using commonly available course artifacts such as syllabi, lesson plans, directions for assignments, and student products as support, faculty can assess the degree to which they employ thirty essential actions that define learning-centered teaching on Blumberg’s (2019) descriptive rubrics. These rubrics also offer suggestions for how to use the results of the data they collected to become more learning-centered, thus closing the assessment loop. When faculty perform these assessments of their teaching they can use the results in their performance evaluations and teaching dossiers.

Author(s)

Phyllis Blumberg, PhD is an internationally recognized educator, presenter, writer, and consultant on promoting deep and lasting learning, learning-centered teaching, assessment of student learning, and effective teaching. Phyllis is an educational consultant collaborating with faculty and staff in all disciplines to enable students’ engaged and deep learning. For 20 years she served as Director of the Teaching and Learning Center at the University of the Sciences in Philadelphia. She also served as assistant provost for faculty and assessment development, research professor in education and psychology, and associate dean for curriculum. She is the author of more than 70 peer-reviewed articles and three books on teaching in higher education: Developing Learner-Centered Teaching: A Practical Guide for Faculty; Assessing and Improving Your Teaching: Strategies and Rubrics for Faculty Growth and Student Learning; and Making Learning-Centered Teaching Work: Practical Strategies for Implementation.

Attachments

References

American Council on Education. (2018). ACE research outlines best practices to support effective teaching and improve student learning. Retrieved from https://www.acenet.edu/news-room/Pages/ACE-Research-Outlines-Best-Practices-to-Support-Teachers-and-Improve-Student-Learning.aspx

American Society for Quality. (2016). Strengths, opportunities, aspirations, results (SOAR) analysis. Retrieved from http://asqservicequality.org/glossary/strengths-opportunities-aspirations-results-soar-analysis/

Blumberg, P. (2019). Making Learning-Centered Teaching Work: Practical Strategies for Implementation. Stylus Publishing, LLC.

Bok, D. (2015). Higher education in America (revised ed.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Boring, A., Ottoboni, K., & Stark, P. B. (2016). Student evaluations of teaching are not only unreliable, they are significantly biased against female instructors. Impact of Social Sciences Blog.

Evergreen, S. (2017). Effective data visualizations: The right chart for the right data. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Felder, R. M., & Brent, R. (2016). Teaching and learning STEM. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Lawrence, J. W. (2018). Student evaluations of teaching are not valid. American Association of University Professors.

Haras, C., Taylor, S. C., Sorcinelli, M. D., & von Hoene, L. (2017). Institutional commitment to teaching excellence. Washington DC: American Council on Education (ACE).

Nilsen. L. (2012). Time to raise questions about student ratings. In J Groccia & L. Cruz (Ed.). To improve the Academy: resources for faculty instructional and organizational development. Vol 31 pp. 213-228. San Francisco: Josey-Bass.

Strobe, W. (2016). Why good teaching evaluations may reward bad teaching: On grade inflation and other unintended consequences of student evaluations. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 11(6), 800-816.

Suskie, L. (2009). Assessing student learning (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Suskie, L. (2014). Five dimensions of quality: A common sense guide to accreditation and accountability. John Wiley & Sons.

Weimer, M. (2002). Learner-centered teaching: Five key changes to practice. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Weimer, M. (2013). Learner-centered teaching: Five key changes to practice (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

No comments yet.