Abstract

Knowing that First-Year Composition (FYC) is closely tied to student success at our Hispanic-serving institution, we conducted a pilot study to see how redesigning our FYC courses with scaffolded reading and writing instruction might impact pass rates and retention of our Latinx students. The results of this study clearly demonstrated that a scaffolded course design that culminates in a final assessment based upon prior knowledge and course content improves students’ skills acquisition and course pass rates.

First-Year Composition for Latinx Student Success

Studies have repeatedly shown that first-year writing is critical for student success and particularly so for Latinx students (Mecenas, 2019; Doran, 2017; Ruecker, 2014; McCracken & Ortiz, 2013; Kirklighter et al., 2007). A recent study on first-year courses shows how performance in writing courses strongly predicts retention and overall student success (Garrett et al., 2017). Livingston & Peña (2020), in their study of Latino male students in first-year writing, contend that the group’s success in future courses is largely dependent on learning how to write at an academic level, and students who do not succeed in these courses will likely struggle in their subsequent coursework. This correlation is found to be consistent at our Hispanic-Serving Institution (HSI). Bronx Community College (BCC) is an open admissions HSI with over a 63% Hispanic population. It not only has the second highest Hispanic enrollment in the City University of New York (CUNY) system but is also an institution with one of the highest concentrations of Hispanic students among the Hispanic Association of Colleges and Universities (HACU) member schools. A recent report by ¡Excelencia! in Education and the State University of New York at Albany stated that BCC is one of the top five colleges across the state for enrolling and awarding associate degrees to Latino students (2021). Moreover, according to the recent reports by the BCC Office of Institutional Research, first-year composition (FYC) plays a key role in retention. Students who pass FYC by the end of their first year are more likely to continue for a second year. For the Fall 2016 and Fall 2018 cohorts, the retention rate for those who passed FYC by the end of their first year is far greater than the retention rate for those who did not pass FYC: +45.3% for Fall 2016 cohort and +47.1% for Fall 2018 cohort (Ballesian, 2020).

To better understand how Latinx students succeed at our HSI, it is important to examine how FYC has evolved at our institution. The pass rates for FYC at BCC were around 70 percent until Fall 2019, but when the pandemic hit, rates fell to 55.8 percent in Spring 2020 and 48.1 percent in Fall 2020. According to the Fall 2020 pass rates report, FYC courses rank as having one of the lowest pass rates in the college (BCC, n.d.-b). Interestingly, the FYC pass rates for Fall 2020 were higher than the rates in Spring 2020, even though student surveys report that students were better adjusted to the pandemic situations in Fall 2020 (Kim & Kessler-Eng, 2021). The pass rates for FYC have still not bounced back for Spring 2021 (BCC, n.d.-b). The key difference for FYC in Spring 2020 was that it was the only semester in which a common English Department final exam was not used as a final assessment.

Rethinking Final Assessment

We conducted this study to see if redesigning our FYC courses by scaffolding reading and writing throughout the semester and having an alternate final assessment would improve students’ pass rates and retention. Currently, our FYC courses use a final common exam that is not based upon individual instructor’s course content. A long final exam reading (5000-7000 words) chosen by a committee is shared with FYC instructors and students three weeks before the exam is given. The exam itself offers a prompt that asks students to write about this long reading and an additional short reading (500-1000 words) given at the time of exam. Students are expected to produce a full essay within 2 hours.

This format of the final exam raises questions about what many Composition scholars have long questioned. First, many scholars have disputed the validity and reliability of timed essay exams as an indication of writing ability (Caudery,1990; Del Principe & Graziano-King, 2008; Lau, 2013), and studies have repeatedly shown how English Language Learners (ELLs) and Multilingual Learners (MLs) have difficulty with timed essay exams since many students lack the implicit language knowledge that allows them to quickly respond to writing tasks (Lax, 2005; NCTE, 2005). Since the timed essay exam does not build upon what the students learned in their respective FYC sections, a timed essay exam contradicts the scholarship of how prior knowledge and context are important for first-year writers and particularly for ELLs and MLs (Cui, 2019; Artemeva & Myles, 2015; Robertson et al., 2012; Reiff & Bawarshi, 2011).

In this context, we designed courses that required scaffolded reading and writing assignments that culminated in a final assessment project that was based upon what students had been reading and writing throughout the semester. Students were asked to explore a central research question of their own choosing within the course’s umbrella theme, which allowed them to rely on the background knowledge they had gained during the semester. The pilot study offered us the opportunity to see if student success rates would improve with such a curriculum and scaffolding.

Research Paper as Gateway to Academic Discourse

When designing our FYC courses, our goal was to be true to the community college mission and offer educational access to students who may or may not be prepared to engage in college-level academic discourse. We designed a curriculum for both traditional and nontraditional students, many of whom had never written a formal research paper. BCC has a sizable nontraditional student population: according to the Fall 2018 data, 55 percent are 1st generation college students, 36 percent of students are 26 or older, 36 percent are enrolled part-time, and 25 percent are supporting children (BCC, n.d.-a). The overall objective was to design an equitable and inclusive curriculum for all students, traditional, nontraditional, ELLs, and MLs.

To this aim, we chose the research paper as a means of final assessment, thereby allowing students to use their prior knowledge and to provide a seamless instructional design. The goal of FYC courses is to introduce students to academic writing that will prepare them to write across disciplines, and many disciplines require students to write research papers in their courses. Additionally, as the prototypical structure for academic prose, the research paper can be one of the most valuable assignments for FYC since the skills needed for research paper writing —identifying the problem at stake, evaluating and analyzing data, synthesizing different perspectives, organizing ideas for maximum clarity —are valued in any kind of career or academic study. If the timed essay exam was designed to measure the skills at the end of the course and produce a summative assessment of students’ writing abilities, the task to write a college-level research paper is indeed the most vital exit skill students need to succeed and, in many ways, the most valuable transferable skill a student can master in FYC.

Using a research paper that is an outgrowth of a semester’s worth of course content and instruction as a means of final assessment is also more equitable than the timed essay exam. Timed essay exams can privilege and validate certain types of learning, and sometimes students who do poorly, preemptively assume that they do not belong in college (Montenegro and Jankowski, 2017). Instead, we believe colleges should assess students to promote learning through critical thinking and find more authentic means of demonstrating what students have learned at the higher levels, e.g., synthesis, analysis, evaluation (St. Amour, 2020). Equitable assessment requires reflection and planning, and what worked for one institution or program may not work at others. Instructional design should be mindful of the student population(s) being served and should not privilege some students’ learning while perhaps marginalizing others (Montenegro and Janowski, 2020). With this in mind, the FYC course in our study was redesigned to be taught in two different sections in Spring 2021 (N=30). The Latinx students in these sections (59% and 61% respectively) were comparable to the college demographic (BCC, n.d.-a). Reading and writing assignments were scaffolded throughout the course, the research paper was designed to be an outgrowth of previous writing assignments, and newly developed rubrics were used to grade student work and summarily assess the results of the pilot program.

Meeting Students Where They Are and Closing the Gap

Instead of considering the learning activities and developing assignments around them to assess the course learning outcomes, our pilot sections utilized the backward design framework to consider the learning outcomes before assignments and learning activities (Bean, 2011; Fink, 2003; Wiggins and McTighe, 2005). With the research paper as the course’s final project, the scaffolding of assignments for our FYC sections was designed to reflect the integrated processes of reading and writing and to add complexity gradually in course assignments. Recent scholarship makes clear that reading and writing are not two separate enterprises, and that to be a successful academic writer, one must also be an astute reader of texts (Carillo, 2015). For college students to actively engage in academic discourse, they should have college-level reading skills. At BCC, the reality is that developmental readers and writers are now being placed into college-level credit-bearing courses like FYC. Hence, the readings in our FYC began with basic texts, such as excerpts from encyclopedias, which help define the theme of the module. Doing so provided students with a vocabulary with which they could discuss the topic at hand. Next, students were introduced to texts that provide historical, social, and cultural context for the learning module’s theme. Additionally, readings that illustrate the pros and cons of specific issues were assigned to help students understand the parameters of the conversation surrounding the issues under discussion (Choi, Kessler-Eng & Todaro, 2019). These readings became a springboard for students to understand and to respond to more complex argumentative texts that rely on prior knowledge.

It was important for both instructors and students to understand that writing is not produced in an orderly, seamless manner. As instructors, we seldom tell our students how writing goes through a messy process, and we often give credit to polished, properly formatted writing. However, as any writer is aware, writing rarely, if ever, takes place in an uninterrupted systematic order. When scaffolding the writing assignments for the research paper, writing as a process was emphasized, and various informal writing tasks were designed to build into the research paper. Examples of these informal writing tasks included submitting recordings of their “think aloud” sessions in their native language (synthesis), identifying reasons and evidence that make up an argument (analysis), and finding the most relevant quotes for their own thesis (evaluation). Gradually increasing the level of difficulty and complexity of the writing assignments throughout the course allowed students to become comfortable with the writing process, and students with developmental needs became more confident in their abilities because the course assignments were manageable for them.

To establish common standards of assessment for our study, a rubric based on the learning outcomes of FYC was developed and utilized to assess the research papers. In consultation with the college assessment coordinator, reading coordinator, writing coordinator, and the current final exam committee, AACU’s VALUE rubrics in written communication, reading, and critical thinking were combined, and benchmarks were adjusted to reflect our student population (Rhodes, 2010, see Table 1). First, the rubric was used to assess the research papers from each of the sections. Second, the overall pass rates were compared against our pilot sections.

Results

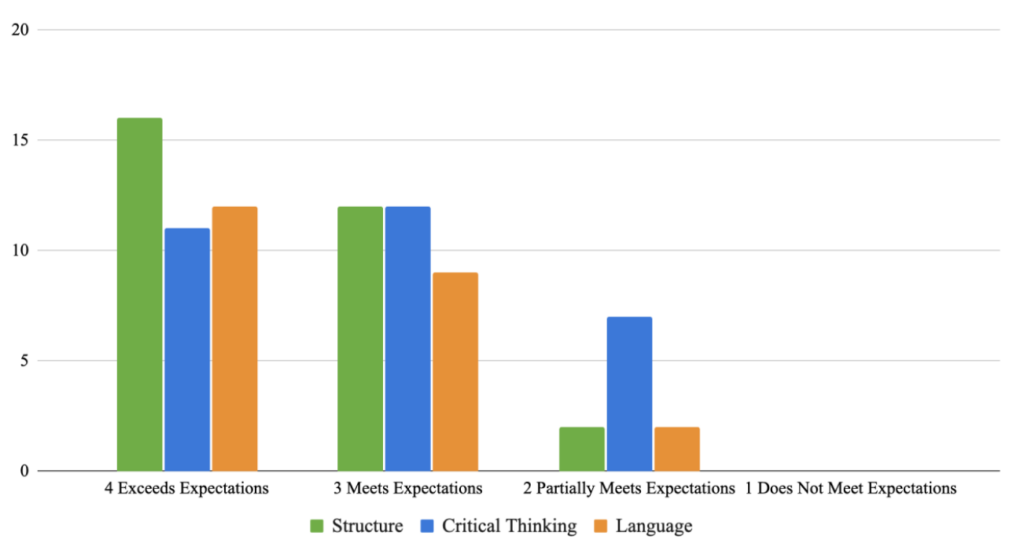

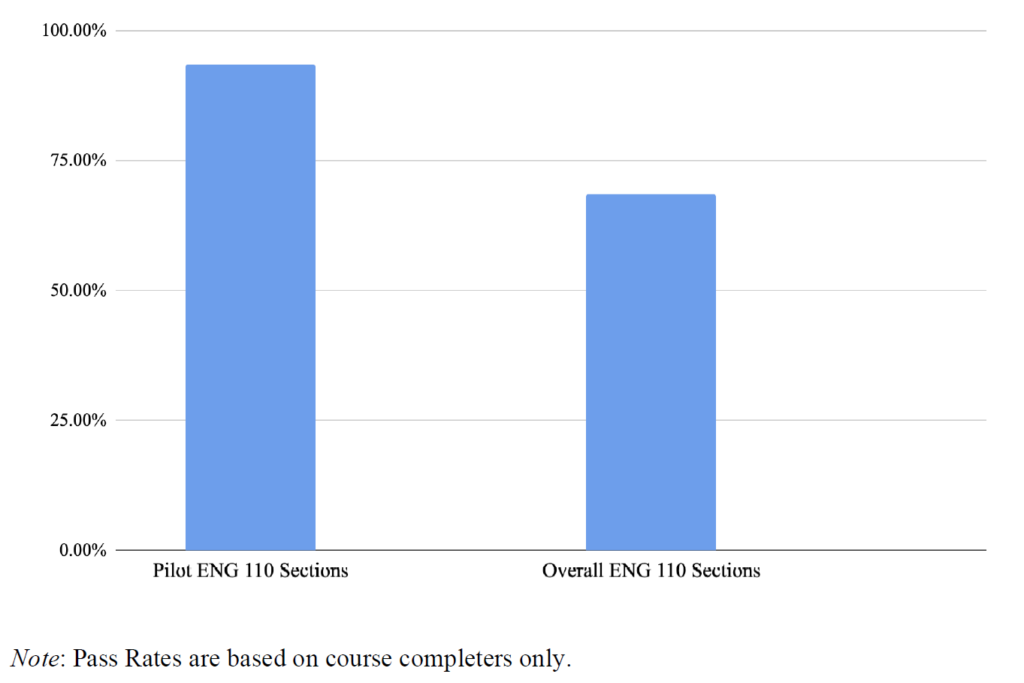

All the research papers in the pilot study scored above the benchmark. In our pre-assessment discussions with the Assessment Council, we arrived at a consensus that a rating of 2, or “Partially Meets Expectations” for all categories (structure, critical thinking, and language), would be the benchmark for our student demographic. In other words, in terms of structure, we assumed that most of the students would be writing with some level of organization but display many digressions, ambiguities, and irrelevances. In respect to critical thinking, the central idea might be vague or too broad and the overall development would not impart enough coherence in analyses and insights. Finally, the language use, or usage of grammar and genre conventions, would often interfere with comprehension. This understanding of the benchmark was consistent with the benchmark used in previous assessments of the FYC courses. However, the pilot sections exceeded this benchmark in every rubric category. As shown in Figure 1, most of the papers excelled in structure: 53 percent received the highest rating of 4 (“Exceeds Expectations”) and 40 percent received a rating of 3 (“Meets Expectations”). The papers also demonstrated strong command of the standards in the language category: 40 percent received a rating of 4 and 30 percent received a rating of 3. For critical thinking, 40 percent of the papers received a rating of 3 and 36 percent received a rating of 4. It is notable that there were no papers with a rating of 1 or fell into the category of not meeting expectations. Furthermore, as seen in Figure 2, when comparing the pass rates for course completers, the pilot sections with the scaffolded reading and writing design (93.5%) were significantly higher than the pass rates for the overall pass rates for the FYC sections (68.6%).

Implications and Recommendations

Overall, the results of the study are consistent with the existing scholarship: the validity of timed essay exams are questionable and prior knowledge and context should be emphasized in FYC curricular design. Our study shows that the scaffolded design with the research paper as the final assessment tool proved to be invaluable in boosting course pass rates. The students in this study’s pilot sections scored considerably higher pass rates than those students in sections that championed the timed essay exam. In other words, students succeeded in FYC if they were given a summative assessment based upon course content, which confirms the importance of course design that helps students build on prior knowledge.

More than three-fourths of the students (76 percent) in this study partially met or exceeded expectations in the critical thinking category and none of the students in this study fell into the “Does Not Meet Expectations” category. The scaffolded reading modules for the courses’ themes provided students with background knowledge and skills they could call on to successfully analyze and discuss complex topics in a research paper. The study showed that 53 percent of research papers received the rating of “Exceeds Expectations” in terms of structure. Students could introduce their topic, define terms, and provide background information and a strong context for the theses in their introductions. Also, students were familiar with multiple perspectives of the course theme as reading modules provided opposing viewpoints. This allowed students to easily locate evidence and address counterarguments.

The strengths of structure and language are attributed to the scaffolded design. In our study, no student fell into the “Does Not Meet Expectations” category, and only 6.6 percent fell into the “Partially Meets Expectations” category for language use. Writing assignments during the semester were divided into multiple steps, often dividing the assignments by parts of the essay structure (e.g., introductions, main body paragraphs, conclusion), which naturally led the students to construct a beginning, middle, and conclusion in their papers. Also, the substantial pre-writing steps in the scaffolding allowed students to minimize digressions, ambiguities, and irrelevances. While both pilot sections utilized sample writings to model correct use of grammar and genre conventions, the scaffolded design allowed both students and instructors to revisit the writing multiple times to address grammar errors and genre conventions. Sometimes students revised the local errors on their own as they were updating the drafts, and instructors were always able to track the local errors through feedback. While critical thinking was the least strong category among the three, 76 percent of papers received a rating of 3 or higher. In other words, thanks to the scaffolded design, all the papers had clear central ideas. The pre-writing assignments such as journaling, summarizing, annotating, and outlining allowed students to practice critical thinking through low-stakes assignments and comfortably build on these ideas when they came to write toward the formal assignment. Critical thinking was also fostered through scaffolded reading. By gradually increasing the complexity of the reading assignments and introducing the students to varying perspectives on the course theme, students gained confidence articulating the topics since all the papers were referring to the reading assignments and reflecting on them.

The results of this pilot study show that students who are provided with integrated reading and writing instruction and a final assessment that is based upon context and prior knowledge are more likely to succeed than those who are not. Nationally, reforms such as the movement toward co-requisite FYC courses (courses that combine FYC with developmental instruction) allow students quicker access to FYC courses. However, access is not synonymous with success in FYC courses, and this is especially true for many Latinx students. To create equity and academic success for all, FYC instruction and the means of final assessment should be reformed as well to ensure student success.

Author(s)

Swan Kim is an associate professor of English and Writing Across the Curriculum (WAC) coordinator at Bronx Community College (BCC) at City University of New York (CUNY). She received her PhD in English at University of Virginia specializing in Asian American diaspora. She teaches courses in composition and ethnic American literature.

Her research interests include WAC/WID, first-year writing, antiracist pedagogy, diaspora and immigration, race and ethnicity, and Asian American literature and culture. She has been serving as the Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion committee co-chair at the Association for Writing Across the Curriculum(AWAC), the co-leader for the CUNY WAC Professional Development, and a faculty senate and council member at her college.

Donna Kessler-Eng is an associate professor of English at Bronx Community College. She teaches integrated reading and writing co-requisite courses, composition, and literature and medicine courses. Her research interests include the history of American medicine and literature, pedagogy, and strategies for community college students’ academic success.

References

Artemeva, N. & Myles, D. (2015). Perceptions of prior genre knowledge: A case of incipient biliterate writers in the EAP classroom. In G. Dowd, & N. Rulyova (Eds.), Genre trajectories: Identifying, mapping, projecting (pp.225-245). Palgrave MacMillan.

Ballesian, E. (2020). A tale of two metrics: Big strides on graduation, no progress on retention. BCC Office of Institutional Research.

Bean, J.C. (2011). Engaging ideas: The professor’s guide to integrating writing, critical

thinking, and active learning in the classroom. Jossey-Bass.

Bronx Community College. (n.d.-a). Facts and figures. https://www.bcc.cuny.edu/about-bcc/facts-figures/

Bronx Community College. (n.d.-b). Pass rate reports. BCC Office of Institutional Research. https://bcc-cuny.digication.com/oir/Pass_Rate_Reports

Carillo, E. C., (2015). Securing a place for reading in composition: The Importance of teaching for transfer. Logan, UT: Utah State UP.

Caudery, T. (1990). The validity of timed essay tests in the assessment of writing skills, ELT Journal, 44(2), 122–131, https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/44.2.122

Choi, M., Kessler-Eng, D., & Todaro, J. (2019, April). Creating a co-req model: Placing reading and writing center stage. Restructuring first-year writing at CUNY: Access and equity in the 21st century. New York.

Cui, W. (2019). Teaching for transfer to first-year L2 writers. Journal of International Students 9(4), 1115-1133.

Del Principe, A. & Graziano-King, J. (2008). When timing isn’t everything: Resisting the use of timed tests to assess writing ability. Teaching English in the two year college 35, 297-311.

Doran, E.E. (2017). An empowerment framework for Latinx students in developmental education. Association of Mexican American Educators Journal, 11(2), 133-154. http://dx.doi.org/10.24974/amae.11.2.353

¡Excelencia! in Education. (2021). A New York briefing on 25 years of HSIs. https://www.edexcelencia.org/25yrs-HSIs-New-York

Fink, L.D. (2003). Creating significant learning experiences: An integrated approach to designing college courses. Jossey-Bass.

Garrett, N., Bridgewater, M., and Feinstein, B. (2017). How student performance in first-year composition predicts retention and overall student success. Retention, Success, and Writing Programs. Ruecker, T., Shepherd, D., and Estrem, H. (eds.) Utah State UP, 93-113.

Kim, S., & Kessler-Eng, D. (2021). Beyond the digital divide: Allowing for the evolution of the college community during the pandemic. Community College Journal of Research and Practice 26. https://doi.org/10.1080/10668926.2021.1972363

Kirklighter, C., Cárdena, D., Murphy, S.W. (Eds.) (2007). Teaching writing with Latino/a students: Lessons learned at Hispanic-serving institutions. SUNY Press.

Lau, A. (2013). Timed writing assessment as a measure of writing ability: A qualitative study. Discussions, 9(2). http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/a?id=798

Lax, J. (2005). The effect of a timed writing assessment on ESL undergraduate engineering students. IPCC 2005. Proceedings. International Professional Communication Conference, 2005., 40-46.

Livingston, M.A. and Peña, E. V. (2020). Latino male students’ perceptions of writing in first year college writing courses. American Association for Adult and Continuing Education.

McCracken, M. and Ortiz, V.A. (2013). Latino/a student (efficacy) expectations: Reacting and adjusting to a writing-about-writing curriculum change at an Hispanic serving institution. Composition Forum, 27. Retrieved from https://compositionforum.com/issue/27/student-expectations.php

Mecenas, J. (2019). Recognizing Institutional Diversity, Supporting Latinx Students: First-Year Writing Placement and Success at a Small Community Four-Year HSI. Open Words: Access and English Studies 12(1), 126-146.

Montenegro, E., & Jankowski, N. A. (2017). Equity and assessment: Moving towards culturally responsive assessment. (Occasional Paper No. 29). Urbana, IL: University of Illinois and Indiana University, National Institute for Learning Outcomes Assessment (NILOA).

Montenegro, E., & Jankowski, N. A. (2020). A new decade for assessment: Embedding equity into assessment praxis (Occasional Paper No. 42). Urbana, IL: University of Illinois and Indiana University, National Institute for Learning Outcomes Assessment (NILOA).

National Council of Teachers of English. (2013). First-year writing: What good does it do? http://mjreiff.com/uploads/3/4/2/1/34215272/nctepolicybrief.pdf

Reiff, M.J. & Bawarshi, A. (2011). Tracing discursive resources: How students use prior genre knowledge to negotiate new writing contexts in first-year composition. Written Communication 28(3), 312-337.

Robertson, L., Taczak, K., & Yancey, K.B. (2012). Notes toward a theory of prior knowledge and its role in college composer’s transfer of knowledge and practice. Composition Forum 26. Retrieved from http://compositionforum.com/issue/26/prior-knowledge-transfer.php

Rhodes, T. (2010). Assessing outcomes and improving achievement: Tips and tools for using rubrics. Washington, DC: Association of American Colleges and Universities.

Ruecker, T. (2014). Here They Do This, There They Do That: Latinas/Latinos Writing across Institutions. College Composition and Communication, 66(1), 91–119.

St. Amour, M. (2020, June). A push for equitable assessment. Inside higher ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2020/06/25/assessment-group-releases-case-study-series-equitable-ways-judging-learning

Wiggins, G. & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design. Prentice Hall.

Fait accompli is a beautiful thing. Luckily these “scaffolds” will accompany students into the “real” world, making this a very useful service. Essentially instructors are grading themselves.

If all else fails, they can work for CUNY.

I guess the idea is that the first year of college is commonly referred to as the first year because typically you then proceed to the next year. You don’t need to leave first year writing being able to write as a college graduate, correct? Students, and all humans for that matter,use the scaffolds for as long as they need them.

With the push to end remedial classes nationwide, scaffolding reading/writing and replacing timed exams seem a viable alternative for community colleges who must be concerned with equitable outcomes.

Did I read through too quickly? What was the number (n) of the overall sections and the pilot sections? Thank you!